A grumpy floof, a gilded railroad spike and Winslow Homer's unrequited love

Plus, a 400-year old walrus ivory ring

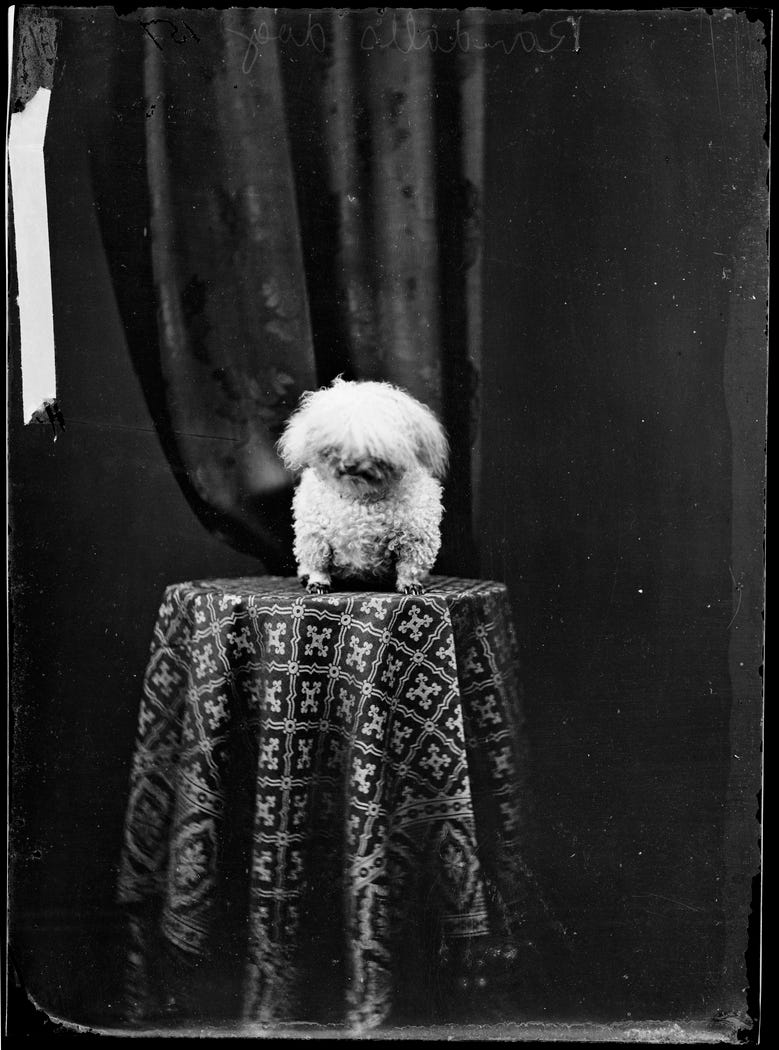

Hello, my friends! I know we’re a few weeks in, but I would like to introduce you to my official 2023 energy:

To be honest it’s not much different than my usual energy, just fluffier.

Hat tip to the wonderful Undine on Twitter for bringing this photo to my attention. A quick bit of research has told me that this little guy — listed officially as “Dog of Randall the jeweller” — is featured in no less than three different ca. 1870s portraits in the Holtermann Collection of photos at the Mitchell Library of the State Library of New South Wales, Australia. The Holtermann collection is a fascinating group of photos that document the early goldfield towns in New South Wales and Victoria from the years 1871 to 1876, as well as some streets and buildings in Sydney and Melbourne. There are also TONS of posed portraits of people and babies, but Randall’s dog steals the show. You can see the second grumpy floof portrait here, the third here, and — just for the sake of completion — this is Randall.

Ok, on to the STUFF. This is the time of the year where we get to see some of the more interesting, eclectic auctions, with less bling and more history. Not that there isn’t SOME bling, though — I can’t not mention the circa 1920 amethyst and diamond cross above that was previously worn by Princess Diana. A substantial piece at over five inches tall and almost four inches wide, the cross dates to around 1920 and was made by Garrard, the royal jewelers who also created Diana’s sapphire and diamond engagement ring.

It’s known as the “Attallah Cross” because Diana first borrowed it in 1987 from Naim Attallah, Garrard’s then managing director, to wear to a charity event. She actually borrowed it a number of times after that, but the 1987 occasion is probably the most famous, because she paired it with her own long pearl chain to accessorize a Tudor-style Catherine Walker dress with a ruffed collar. (Warning: the dress is so ’80s it may reach out from the screen and try to strangle you with a Benetton rugby shirt.)

The cross was included in the Sotheby’s Royal & Noble sale in London last Tuesday, and it carried an estimate of £80-120,000 ($99-149,000). After five minutes of bidding between four buyers, it sold for £163,800 ($197,453) to none other than Kim Kardashian, so we’re bound to see it again at some point.

Circa 1600, this English seal ring is made of walrus ivory and features the arms of Gilbert, Earl of Shrewsbury (1552-1616). The arms are placed within a garter motif, because Gilbert (a fairly unpleasant sort who apparently fought with everyone: family, tenants, Queen Elizabeth I, etc.) was made a knight of the garter in 1592.

While it does have a cracked shank and some other surface damage, it’s amazing this ring has survived as long as it has, considering the age and fragility of the material. It was estimated at £3,000 - £5,000 ($3,730 - $6,214) in the Sotheby’s London Emma Hawkins: A Natural World auction last Thursday and sold well above average for £11,970 ($14,876).

Now this is interesting. If you’re one of my earlier subscribers, you may remember that back in 2019, I featured a circa 1887 octopus chatelaine by Gorham. A chatelaine — in case you missed that old post — is basically a central pin or clip with various hanging attachments that hold essential everyday tools: scissors, pencils, pincushions, watches….whatever a woman might need throughout the course of her day. The attached tools could easily be personalized, so chatelaines soon evolved to suit tons of specialties, including needleworking, nursing, painting, etc.

Because a chatelaine’s tools were so easily swapped around, they were also easily lost or repurposed, and few have survived with all their original bits. The chatelaine above — which is included in the Bonhams Los Angeles Curated Curiosities | Live Online sale tomorrow — is the same hallmarked Gorham chatelaine (which is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art) that I featured back in 2019, but this one has had a series of carved bone fish added to it at a later date.

So somewhere along the line, the chatelaine lost some or all of its original undersea-themed tools from Gorham, and somebody decided to update it into a different, whimsical piece of jewelry. This marriage of parts is reflected in the estimate of $800-1,200. (For comparison, a complete original version of this chatelaine — which you can see in my 2019 post — sold at auction in 2012 for $10,000.) I’m curious to see what happens with this one.

[Also, quick note because I know some of you are collectors: There is a TON of Bakelite in this Curated Curiosities sale. The pieces start around lot 120 and from that point on it’s all Bakelite, all the time. Have fun!]

This odd thing was immediately recognizable to me as a railroad spike — something my older siblings regularly used to bring home from their ramblings along the old train tracks that ran through the woods in our neighborhood.

They never brought home one that looked like this, though. This is the Arizona Spike, and it was one of four gold- and silver-clad ceremonial spikes presented at the festivities celebrating the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad. The spikes were used to mark the “meeting of the rails” at Promontory Point, Utah on May 10, 1869, and this one is ornately inscribed:

Ribbed with Iron, Clad in Silver and Crowned with Gold

Arizona presents her offering

to the Enterprise that has banded a Continent

and dictated a Pathway to Commerce.

Presented by Governor Safford

The event marked the historic joining of the two rail lines that provided travel between California and the cities of the East Coast of the U.S. The rails were laid by two companies: Central Pacific, which began work in Sacramento and progressed eastward, and Union Pacific, which was working westward across the Great Plains from Omaha.

The two rival companies didn’t play well together, so when they couldn’t agree on a meeting point, Congress did it for them. The day of the joining festivities was scheduled for May 8th, 1869, but the event was postponed for two days because the car holding the Union Pacific officials was deliberately decoupled from the train in Wyoming by a group of railroad workers who hadn't been paid in five months. Once Union Pacific scraped up the $80,000 cash the workers were owed, the car got back on track. (Just another moment in our long U.S. history of treating railroad workers like crap.)

There’s so much more to the story of this spike — including how it went missing for years, and there may be a copy???? — but I don’t have the space for it all here, so if you’re into it, click through to read the lot essay!

The spike is included in Friday’s The Exceptional Sale at Christie’s New York, and it carries an estimate of $300,000–500,000.

Circa 1765, this sweet little French enamel, ruby and diamond ring was probably a betrothal ring. Featuring a pair of white doves sitting within flowering branches in shades of black, white, green and deep blue enamel, it also includes accents of rose-cut diamonds and cushion-shaped rubies. The back of the ring has an enameled inscription, but it’s impossible to make out.

There’s a similar dove ring from the same time period in the collection of the British Museum, and that one features an inscription around the band that says UNIS A JAMAIS, or “forever united,” which contributes to the theory that these rings were betrothal gifts.

The ring is included in the second day of the Wooley & Wallis Salisbury Fine Jewellery sale taking place on February 1-2, and the estimate is £800-1,200 ($990-1,486).

Remember that Cartier “Mauna” necklace I was raving about last month? One of the main reasons I loved it was the unexpected use of rutilated quartz as a backing plaque for the main pendant. Rutilated quartz is one of my favorite gemstones — its tiny, needle-like inclusions (composed of a mineral called rutile) can appear in various colors including silver, black, copper or gold, and their scattered distribution provides the stone with an incredibly striking appearance.

Circa 1913 and also by Cartier, the Art Deco desk seal above is a fantastic example of the stone, which has been cut in the clean, geometric form of a plinth or pedestal to allow the beauty of the quartz to speak for itself (although the Cartier designer has given in to a few rose-cut diamond embellishments).

The seal itself is engraved with a ducal and a royal coat of arms, signifying the marriage between Archduchess Mechthildis of Austria (1891-1966) and Prince Olgierd Czartoryski (1888-1977). She was a Habsburg and he was a Polish prince, and they had four kids and lived in Poland until 1939, when the prince was sent, along with other Polish aristocrats, to a German concentration camp. He escaped (I don’t know how; he just mentioned it in passing in a ca. 1943 letter to the New York Times) and the couple fled to Brazil. They were together for 53 years until her death in 1966.

The piece is also included in the Woolley & Wallis Fine Jewellery sale on February 2, and it’s estimated at £6,000 - £8,000 ($7,449 - $9,933).

On February 10, Heritage Auctions in Dallas is holding a live auction entitled “The Gilded Age: Property from the Collection of Richard Watson Gilder and Helena de Kay Gilder.” The lots are already open for bidding, and they include a mix of items from the late 1800s that belonged to the influential couple.

Richard Watson Gilder (1844–1909) was the editor of the illustrated periodical Scribner’s Monthly — which later became The Century Magazine — and his wife Helena de Kay (1846–1916) was a painter and socialite whose weekly salons were frequented by some of the greatest writers, painters, sculptors and actors of the day. Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Samuel Clemens, Louis Comfort Tiffany (his daughter Louise actually married the Gilder’s son, Rodman), Stanford White, Cecilia Beaux, Albert Pinkham Ryder and Grover Cleveland were just a few of the distinguished names that met up at the couple’s homes in Manhattan and Massachusetts.

Helena fervently believed that the prevailing art sensibility of the day was too conservative, and her salons eventually led to her helping launch the Art Students League of New York and the Society of American Artists. She and her husband, according to Columbia University art historian Page Knox,

“played a uniquely progressive role in the late nineteenth century, participating in the meteoric rise of print media, helping to establish and promote a new American art world, supporting female artists, illustrators and critics, and acting as the cultural tastemakers of their time.”

But while they championed women artists, they did NOT approve of the expansion of women’s roles outside the home. Susan E. Marshall notes in her book Splintered Sisterhood: Gender and Class in the Campaign against Woman Suffrage (University of Wisconsin Press, 1997) that while Richard Watson Gilder did support expanded educational opportunities for women, he believed them to be “guardians of the nation’s morality,” and refused to run any pieces that might “offend” mothers or “corrupt” their daughters. He (and Helena) also opposed women’s suffrage:

Gilder editorialized against women suffrage as a threat to the “home woman,” idealizing the female function as a necessary anchor of stability in a changing world.

That’s a load of exhausting nonsense, of course, but whatever. The auction is worth scrolling though; it’s an excellent capsule collection of the late 19th century, with a mix of artwork, ephemera, and interesting possessions — including Helena’s wedding chest (my fingers are itching to root through all the stuff in there) and the piece shown above, an 11k gold “friendship” ring that was said to have been given to Helena by Winslow Homer.

The ring is engraved AMI POUR LA VIE (“friends for life”), and it’s believed that the painter tried to win Helena’s hand prior to her wedding to Richard. Historian Sarah Burns dove into a cache of letters between the two for a 2002 article in The Magazine Antiques, and poor old Winslow certainly comes out of it sounding like a forlorn rejected suitor who then went on to a lifetime of dedicated bachelorhood.

OH! Also — in April, Heritage will be selling Four Brooks Farm, the Gilder’s 159-acre summer home in the Berkshires. The house and particularly the outbuildings are clearly a huge money pit, but the VIEWS. Dear god, the views.

That’s it for this time, guys. I hope this email arrives to you as intended — I keep getting panicked resends of other newsletters I subscribe to, because apparently Substack is having draft issues? Or something. I honestly can’t be mad at them right now because they just debuted a tool that shows us (roughly) where our readers are located, and I was stunned and delighted to discover that Dearest is being read on every continent except Antarctica. I’m a completist, so if you know any south polar penguins who can read, please forward this over to them.

Enjoy the rest of your week!

Love, M xx

Your Substack newsletter is my favourite! Thanks for the thoughtful links and your meticulous attention to provenance, the Diana photos made my day!

The octopus's face! And thanks for the shout out. Dad's poor lawnmowers took a beating from those stray railroad spikes. Whoopsie!