Antique betrothal rings, the Dancing Marquess and some octopus spoons

Also: Please don't miss the bear bench.

Happy belated Valentine’s Day, my friends! I hope you celebrated the chocolate-infused feast day of a beheaded Roman priest in whichever way you prefer, whether that be joyfully, sneeringly or blissfully cluelessly.

In honor of the nonsense holiday, let’s talk about fede/gimmel rings! The above ring dates to the 16th-17th century and is in the collection of the British Museum. It’s a combo of two types of ring, the fede and the gimmel. Fede (Italian for “faith”) rings feature a clasped hands motif that dates back to ancient Rome and represents the joining of two hands in betrothal, while gimmel rings are essentially puzzle rings formed of two (or sometimes three) interlocking parts. They take their name from the Latin “gemellus,” meaning “twin,” and also were often used as betrothal rings — the engaged couple would each wear one half of the ring, and then reunite the parts at the wedding. The Met has a gorgeous example of a 16th century German gold, ruby and emerald gimmel ring that features two parts that fit together and conceal an inscription that states (in German), “Those whom God hath joined together let no man put asunder.”

The British Museum ring above opens to reveal a heart clasped in one hand and a hidden inscription that says, “As hands be shvt so sewerly knyt,” or “as hands be shut, so surely knit.” The combination of both the fede and gimmel elements point to this ring being used in a wedding ceremony.

The fede/gimmel style (and its Claddagh ring cousin) maintained its popularity through the 19th century and continues today — this ring dates to around 1990 and incorporates a third interior band with a heart. Keep your eyes peeled for them out in the wild; a few years back I found a tiny gold three-band Victorian fede/gimmel at an antiques mall for $80 (!!!). The dealer DIDN’T KNOW IT OPENED and nearly had a heart attack when I showed her how it worked.

This circa 1890 English tiara features approximately 106.8 cts. of old European, old mine, old-cut pear-shaped and rose-cut diamonds set in scroll and cluster motifs in silver and gold. The bottom row of graduated diamonds detaches, so it can be worn separately as a rivière necklace.

It’s known as the Anglesey Tiara, and in the late 19th century it was owned by Henry Cyril Paget, the 5th Marquess of Anglesey. According to the BBC, Paget inherited an estate worth £535,000 — equivalent to about $83 million today — when he was in his twenties, and within five years he had blown the lot, declared bankruptcy and died of tuberculosis-induced pneumonia at the age of 29.

Paget — who was known as The Dancing Marquess — loved the theater, and often played the central role in free plays and performances for the public. He lost most of his fortune by spending millions on sets and costumes:

“He didn’t understand the concept of costume jewellery — he thought it all had to be real,” explained actor and writer Seiriol Davies, who wrote and performed an acclaimed musical show based on the life of the marquess.

“He bought a car that converted the exhaust fumes into rose-scented perfume, he had a fleet of poodles. He made a ping-pong jacket and wanted it to be green — so he made it out of real emeralds,” added actor Davies.

A FLEET of POODLES.

Most of Paget’s jewels and extravagances were sold off to pay his debts, but the tiara stayed within the family after his death, when his estate passed to his cousin Charles. Cecil Beaton photographed Charles’ wife Lady Marjorie wearing it (scroll down) for a feature in British Vogue on the coronation of King George VI in 1936, and it was later worn at the 1952 coronation of Queen Elizabeth II by Dame Shirley Paget, the 7th Marchioness of Anglesey.

Circa 1850, this beautiful French bracelet is an excellent example of piqué work, which is a decorative technique in which tiny pins of gold or silver are inlaid into tortoiseshell. Tortoiseshell is malleable when heated, so the pins can be easily pressed into the piece and are then held in place once it cools.

Piqué designs range from intricate geometric patterns to delicate florals, and the technique was initially seen in France in the 17th & 18th centuries. It later became enormously popular in Victorian England, where it evolved from being hand-made to machine-made (and in the process lost some of the more intricate and asymmetrical detail).

As per usual (at least with anything involving the human race), the popularity of tortoiseshell resulted in the source, the Hawksbill tortoise, being hunted nearly to extinction. It’s now a protected species, with all turtle products banned from trade by the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES).

Last week, Sotheby’s Hong Kong held an auction of snuff bottles, and it’s worth scrolling through to marvel at the different materials, styles and skill on display. The above Qing Dynasty bottle dates to the 18th century and is made of faceted hair crystal. (There’s next to no extra info included with the lot, but the “hair crystal” looks a lot like tourmalinated quartz, which is rock crystal that features needle-thin hairlike inclusions of black tourmaline).

The bottle has a glass stopper and sold for $22,750, well above its high estimate of $1,934. Also, don’t miss the inside-painted bottles, which feature designs painted on the interior of the bottle by extremely skilled artists using narrow brushes with just one or two hairs.

These wonderful sterling octopus teaspoons are hallmarked for 1893 and 1894, and were created by the Yokohama, Japan manufacturer Sadajiro (of) Musashiya. The British retailer Liberty & Co. had an import relationship with Musashiya, and these spoons were shipped to London and hallmarked for Liberty in accordance with British hallmarking regulations. They also feature a separate “S.M.” mark for Sadajiro Musashiya. The 12 spoons are actually two separate sets of six; each set complete with its own original Liberty & Co. case.

Musashiya was renowned for naturalistic designs and — in addition to the charming and totally individual little octopi finials — these spoons feature bamboo-style handles and bowls that are modeled to resemble abalone shell. Liberty sold this set for twice the amount of money they charged for their other silver spoon sets, and you can see an original ad in this article (pdf) by Simon Moore for the Silver Society of Canada. Click through to the article to also see an extended octopus set that includes a pair of sugar tongs, as well as a selection of some of Musashiya’s other gorgeous work.

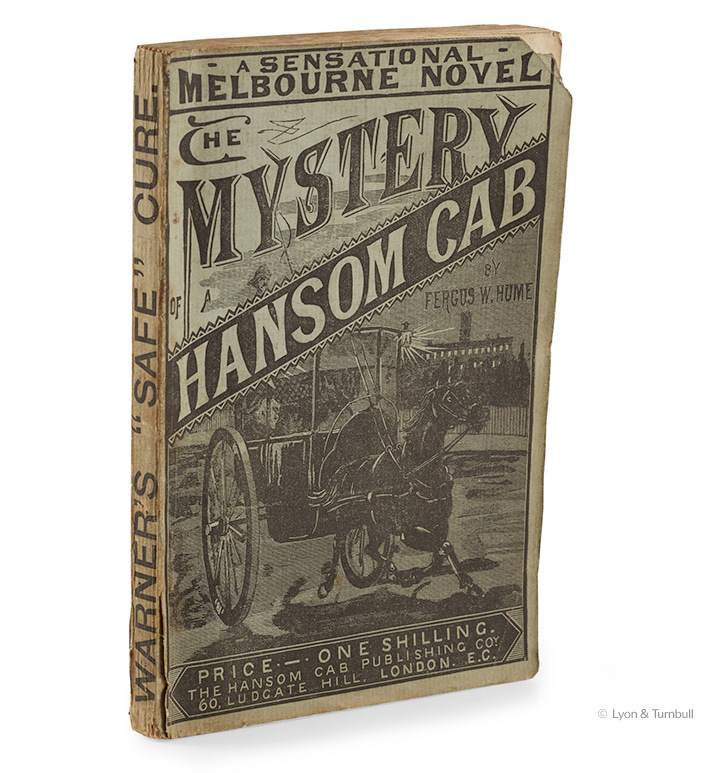

So the other day I was having a root through Lyon & Turnbull’s upcoming Rare Books, Manuscripts, Maps & Photographs auction (live online February 24 - 25), and this book caught my eye. It’s got a great cover, and I wondered what was up with the “Hansom Cab Publishing Company” — was this an advertising vehicle or something? I dunno. I went to bed.

But guess who popped up the next day on my Twitter feed? None other than Otto Penzler, owner of the brilliant Mysterious Bookshop in Manhattan, talking about THAT SAME BOOK — so clearly the universe was telling me to write about it. If you’re a Dearest long-timer, you may remember I first told you about Penzler back in 2019 when he was auctioning off much of his personal collection. More recently, he’s been giving weekly talks on rare books on YouTube, and they’re a delight. Last Thursday, he chose to focus on The Mystery of a Hansom Cab by Fergus W. Hume, and that’s how I learned that this book was actually the best-selling detective novel of the 19th century. (Although Penzler has some suspicions about that...)

Hume, who cultivated an excellent mustache, was born in England but moved with his family to New Zealand when he was a child. He studied law and eventually made his way to Melbourne, Australia, where he became a barrister’s clerk and, in his spare time, a frustrated playwright. Unable to get any theater managers to even read any of his stuff, he decided to try a detective novel instead, and in 1886 he wrote and self-published The Mystery of a Hansom Cab. The book was an unexpected success, with 5,000 copies sold in three weeks. Sales eventually reached 20k in a year, and as Hume didn’t think the book would have much reach outside of Australia, he sold the British and American rights for £50. That was obviously a bad move — but I’ll let Penzler tell you the rest, because I know you, and right now you deserve to take a 15-minute break to chill out and listen to a pleasant human being talk about some books.

The Lyon & Turnbull copy is a second edition (marked “Seventy-Fifth Thousand” at head of title) by the Hansom Cab Publishing Company, and it’s estimated at £400 - £600 ($554 - $831).

I couldn’t be more delighted by this sleek Art Deco frame surrounding a depiction of a ping-pong game. Circa 1930, this table tennis medal is made of an unspecified metal and is just a little over an inch and a half tall, so it would make for a very fun little pendant.

This Swiss “Black Forest” carved and stained walnut bench consists of two glass-eyed bellowing bears supporting a seat with a pierced back. The back features two additional carved bears that are separated and framed by a tree motif, and carved pinecones adorn the armrests. Christie’s London dates the bench to the first half of the 20th century, and it’s included in their “Patrick Moorhead: Hidden Treasures” online auction running from February 4 - 25. Moorhead is a longtime antique dealer and collector, and this auction features a number of pieces he’s picked up over the years. It’s almost entirely Insane Rich People Nonsense, but I swear to god this bench is the best thing I’ve ever seen, and you would not be able to chisel my ass out of it if it were mine.

This [Evil Disney Queen] ring features a 105.45 ct. cabochon rubellite tourmaline nestled in an elaborate setting of intertwined leaves studded with circular-cut tsavorite garnets and pink and orange sapphires. A pavé-set diamond serpent with green gemstone eyes weaves its way through the foliage and around the enameled band.

The ring is French and was made by Victoire de Castellane for Dior, and is included in the Knightsbridge Jewels auction at Bonhams London on February 17. It’s also an excellent example of why you should always look at ALL the photos of a piece, just so you can see exactly how big a 105 ct. tourmaline really is:

YET AGAIN I’m pushing the Substack email length allowance to its very limit, so this has to be it for me today. I hope you’re all well and as happy as possible in the midst of this bleak February. Hit reply if you would like to chat, and, as always, feel free to leave a comment or find me on Twitter at @rococopacetic. Have a good week, everybody! xxx

Thanks for reading, and if you haven’t already subscribed, sign up here:

Monica! As always, what a stunning collection you've put together for us. I'm a little depressed now though, because I have to live the rest of my life knowing I don't own even one of the octopus spoons, let alone the full double set, and sugar tongs, et al. It's a cruel world! Thanks also for sharing the Mysterious Book Shop channel. Between this and that gorgeous Italian jewelry designer, you are now the official curator of my YouTube time!

I want to inside-paint something.....