BATS!

Give them a break, already.

Bats have come in for some bad press in 2020, which is deeply unfair since they’ve just been doing what they’ve always done — sleeping, eating mosquitoes, being the night, etc. — and it’s totally not their fault that human beings are invasive, despicable morons. So, this year I figured I would try to make it up to them and show my appreciation for their whole *waves hands* thing with a special bat-tastic Halloween edition of Dearest. (Note: Not all of the items featured this time are for sale — some reside in museum collections or were sold in past auctions.)

Starting off, this spectacular ca. 1899-1900 Art Nouveau “Butterflies and Bats” pocketwatch by René Lalique sold at Christie’s back in 2002 for $207,500. The watch is gold and features enameled blue and white butterflies on the face, with a cloud of purplish-blue enameled bats flying pell-mell across the reverse. Bezel-set moonstones are scattered throughout, and the piece is finished with a finely detailed coiled serpent that serves as the watch bow (that’s the part that connects to the watch chain).

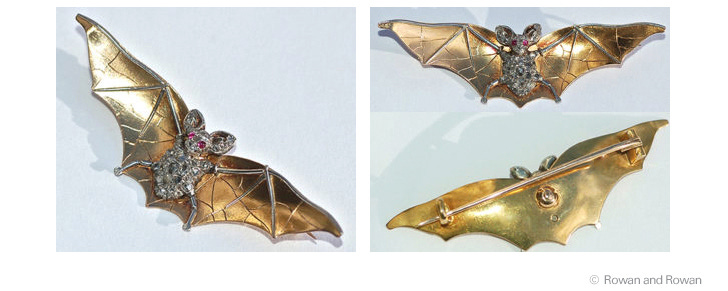

Ca. 1900, this sweet Edwardian long-eared bat brooch has ruby eyes and a plump little silver and rose-cut diamond body. The wings are 15k gold, and 2 1/8” across.

No actual bat here, but a bat-wing motif instead. According to Wartski, this paperknife was purchased by the Dowager Tsarina Marie Feodorovna from Fabergé in St. Petersburg on December 17th, 1899. It was made by famed Fabergé head workmaster Mikhail Perkhin, and features a blade carved from a piece of Siberian nephrite. The yellow gold stylized bat-wing handle has a central oval cabochon ruby placed on each side, and three cabochon moonstones at the edges.

This vintage Asian bracelet pairs a carved carnelian bangle with a brass overlaid band that’s decorated with two stylized bats and tiny incised flowers. It’s only $64, so somebody please buy it before I do.

Bats are considered a good omen in Chinese mythology, signifying good fortune and happiness. This brooch features a translucent mottled green jadeite “bi” (a flat jade disc with a hole in the center) cradled by a 18k white and blackened gold bat. The bat is pavé-set with black and brilliant-cut diamonds and has circular-cut ruby eyes.

Ca. 1900, this Art Nouveau bat pendant is made of finely-carved ivory. It was sold at Bonhams London back in 2014, and was previously owned by the Tadema Gallery, who attributed it to Belgian silversmith and jeweler Philippe Wolfers (1858-1929). The son of a goldsmith, Wolfers became a key figure in Belgian Art Nouveau and was a well-known name in his time. He started out concentrating on jewelry and was known to have worked with ivory in 1897, and later in life moved on from jewelry to sculpture, furniture and metalwork, becoming one of the few Art Nouveau designers who was able to successfully adapt along with changing tastes to the more abstract and geometric style of Art Deco.

The pendant is suspended on a (later) snake-link chain, but the chain isn’t pictured. Seen this way, without it, the piece is almost talismanic. I want it.

This ca. 1900 French Art Nouveau necklace features the Greek goddess Persephone, who we all know ate a curséd pomegranate that resulted in her living half the year in the underworld and emerging for the other half to reunite with her mother Demeter. Persephone’s story symbolizes rebirth and the change of seasons, and this 18k gold necklace depicts her as a young maiden with bat wings of blue plique-à-jour (translucent) enamel. An additional reference to the underworld in seen in the four tiny bat links of graduated blue enamel and gold that are set into the chain.

“On the bat’s back I do fly

After summer merrily.”

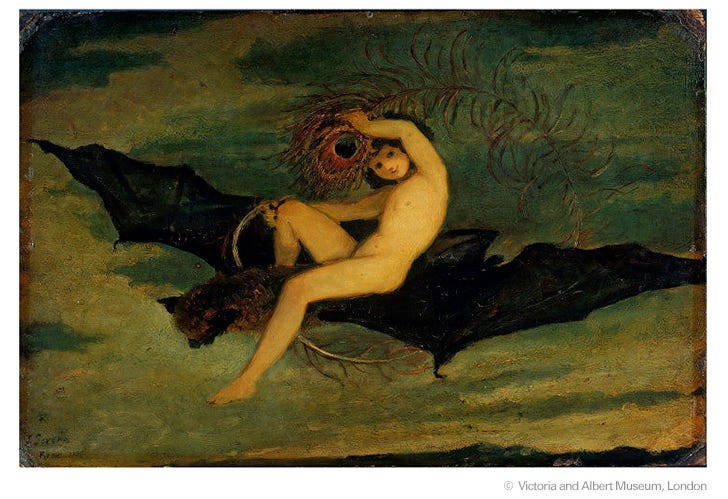

This shell cameo brooch is a depiction of the Act V, scene I song of Ariel the sprite in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Ca. 1840 and set in an elaborately scrolled gold frame, the cameo is exquisitely carved; the artist has managed to represent the fragility of the bat wings and the feather in Ariel’s hand by painstakingly removing the opaque layer of shell down to the faintest level of transparency. The piece is in the collection of London’s Victoria & Albert Museum, and they believe it came from the studio of Tommaso Saulini (1784-1864), one of the best-known cameo artists in Rome during the mid-19th century. Saulini did commission work for Queen Victoria herself, including this double portrait cameo of she and Prince Albert in the Royal Collection Trust.

The Ariel cameo closely resembles another piece in the V&A’s collection:

Cameos were a popular Grand Tour purchase, and their designs were often borrowed from earlier artworks. This particular cameo was clearly inspired by the above 1826 oil painting On the Bat's Back I Do Fly by English artist Joseph Severn (1793-1879). Severn was a close friend of John Keats, and in 1820 he accompanied the sickly poet to Rome and nursed him until his death the following year. Severn stayed on in Rome for another two decades, developing a thriving painting career and helping to establish the British Academy of the Fine Arts in Rome. He fell on hard times when he returned to England in 1841, but was later appointed British Consul in Rome, and was generally successful despite having to navigate the rough waters of Italian unification. He died in 1879 and is buried next to Keats in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome.

This sterling Man in the Moon brooch, ca. 1904, was made by Unger Bros., a jewelry and silversmith firm located in Newark, NJ that was popular at the turn of the last century, and particularly renowned as a manufacturer of American Art Nouveau designs.

Most people associate the name “Wedgwood” with their ubiquitous pale blue and white cameo-inspired jasperware, but the company was also responsible for the elaborate flight of fancy you see above. It’s part of the amazing Wedgwood “Fairyland Lustre” series, which was the creation of a woman named Daisy Makeig-Jones.

Makeig-Jones (1881–1945) was born into a large and well-off family in Yorkshire, and from the start she wasn’t interested in becoming a dutiful Victorian housewife. She had a natural artistic ability that was encouraged both by her family and her art instructors, so when an uncle suggested she might like to be a ceramic artist, she accepted his offer of an introduction to Cecil Wedgwood, the current managing director of the firm and the great-great-grandson of founder Josiah. Cecil was a strict but fair employer who was loved by his workers, and according to Una des Fontaines, the author of the book Wedgwood Fairyland Lustre: The Work of Daisy Makeig-Jones, he was fine with Daisy joining the staff, but he warned her that she would have to start at the bottom and learn her way up. That meant she would be training alongside actual children — who usually started at the factory at the age of 12 or 14 — and, coming from a comfortable background, she might not like working in a factory.

Daisy tartly replied that she “had not consulted him as to whether she would enjoy it,” and so in 1909, she moved to Staffordshire to begin her career at Wedgwood. By 1914 she was a full designer at the firm, complete with her own studio. Her forceful personality and close friendship with the Wedgwood family — her brother also eventually married one of Cecil’s daughters — certainly helped her career, but she had the artistic chops and the imagination and curiosity to back it up. Once she’d gotten her feet under her at the factory, she began to experiment with new techniques and glazes, and started to turn her lifelong love of fairy tales into works of art.

Her Fairyland Lustre series throws together elements from countless sources — fairy and nursery tale illustrations, Asian dragon and Celtic motifs, nature, and simply her imagination — and pairs them with Wedgwood’s gorgeous shimmering metallic lustre glazes. The result is pottery that teems with life and color. The series debuted in 1915 and was an immediate success, boosting Wedgwood’s sales (which had been flagging) and providing the public with a bright, cheerful distraction from the throes of World War I.

The Malfrey pot (or ginger jar) and cover above is from the 1920s and sold this past February at Skinner for $18,750. It features the “Ghostly Wood” pattern, which depicts the Land of Illusion described in The Legend of Croquemitaine — a French tale in which Mitaine, the goddaughter of Charlemagne, has to travel through the Land of Illusion and eventually conquer the Fortress of Fear. Daisy’s design conjures up an infernal landscape of ghastly trees that harbor elves, demons and bats, while cloaked apparitions drift around “holding the flaming candle of their souls,” according to a descriptive pamphlet she wrote up for Wedgwood retailers. Daisy wasn’t afraid to mix up her references, though — look closely and you’ll see the White Rabbit making a break for it at the bottom right.

Daisy designed for Wedgwood for almost 20 years. In 1930, a new Wedgwood (Josiah the 5th) became managing director, and he wasn’t a big fan of the Fairyland series. Neither, unfortunately, was the public, as tastes had begun to evolve, and budgets were tightened after the 1929 crash. Plus, those lustre glazes were expensive, serious work — the piece above probably went through at least six or seven separate firings — so Daisy’s days were numbered. She was asked to retire, but in her indomitable way she completely ignored the request and kept working. This eventually resulted in a huge blowup with Josiah and she did finally leave — but not before she had all of the molds and remaining pieces in her studio smashed to bits.

Wedgwood tried to revive the Fairyland line in the 1970s, but it all came out flat and ugly because they can’t use lead anymore. I REALLY would like to go into the whole history of metallic lustre (or luster) glazes because it’s fascinating, but I don’t have space, dammit. So feel free to look it up — it goes back to the 9th century and it’s basically alchemy.

I’ll leave you with a tiny bit of adorableness, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This beautifully carved 19th century Japanese wood netsuke depicts a mother bat with her two wee babies. Invented in 17th century Japan as a utilitarian item of dress, netsuke were originally tiny sculptural toggles that were used to secure a sagemono — an external pouch or box that was suspended by a cord from the wearer’s obi, or sash. Kimonos didn’t have pockets, so the sagemono served as a small portable storage unit for everyday items, and the netsuke was attached to the top of the sagemono’s cord to keep it from slipping off the obi. The strictly utilitarian use of netsuke declined as traditional Japanese dress transitioned to European, but they continued to be produced as objects of pure artistry and craftsmanship. They can be found in a huge variety of subjects and materials including ivory, boxwood, tusk, amber and pottery, among many others.

Ok that’s it, my friends. Good luck making it through what is sure to be a brutal week and enjoy the full moon on Halloween. Please offer up your best spells and incantations for a swiftly resolved and fortuitous Election Day, and always remember to have a good stretch before you nap. As usual, feel free to leave a comment, reply to this email, or find me on Twitter at @rococopacetic.

Take care of yourselves and stay safe. xxx

Thanks for reading, and if you haven’t already subscribed, sign up here:

I GOT THE BAT BRACELET!!!! I will care for it lovingly and take many beautiful pictures of it

Excellent! Monica, your writing style is wonderful. The story of Daisy Makeig-Jones of Wedgwood was very interesting. I never realized that the Company produced anything other than the cameo-style pieces.