How Tiffany Almost Tanked

And how window designer Gene Moore helped save it. (Also, do you know what a purdonium is?)

On January 26, Sotheby’s New York will feature a collection of silver and enamel circus-inspired pieces by Tiffany & Co.’s Gene Moore in their Important Americana auction.

Gene Moore was Tiffany’s most celebrated window designer. Born (to his dismay) in Birmingham, Alabama in 1910, Moore made his way as a young man to New York City, where his window dressing career started with an assistant position at the I. Miller chain of shoe stores. Over the next couple of decades, he began to make a name for himself, first working for Bergdorf Goodman and then moving on to Bonwit Teller, while also taking classes at the American School of Ballet, to “learn how to get in and out of those windows without knocking everything over.” In 1955, he was coaxed over to Tiffany & Co. by their chairman, Walter Hoving.

Hoving — who had previously done executive stints at various big department stores including Macy’s, Lord & Taylor and Bonwit Teller — had also just started at Tiffany. Despite being one of America’s oldest (founded in 1837) and most respected businesses, profits were declining and the company — which had held on way too long to Art Nouveau and lost the style cachet it once had — wasn’t looking great. Cue Hoving, who had been observing all of this from his presidential suite next door at Bonwit’s. He stepped in, bought up the majority shares of the company, and immediately threw a huge fire sale, unloading everything in the store he felt was outdated and old fashioned. He then hired powerhouse designers Jean Schlumberger, Elsa Peretti and Gene Moore, telling Moore: “I want you to make our windows as beautiful as you can according to your own taste ... Above all, don’t try to sell anything; we’ll take care of that in the store.” (And they did: Under Hoving, sales increased from $7 million in 1955 to $100 million when he stepped down in 1980.)

Moore took Hoving’s instructions and ran with them. By the time he retired in 1994, he had created more than 5000 windows, consistently mixing playful themes and often unconventional materials in designs that guaranteed a double-take. His obituary in the Economist quotes him as saying “Windows should be polite, because they talk to strangers,” but he also deliberately threw in some ringers — broken glass was one of his favorites — to see if people were paying attention (and they were, judging by the phone calls). He also brought in artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns — with whom he’d previously collaborated at Bonwit’s — using the relatively small Tiffany windows to create exquisite little still life compositions.

Over the years, Moore also branched out and did side projects — designing jewelry, ballet and theater costumes and sets, museum exhibits and, just prior to his time at Tiffany & Co., he also took one of the most iconic photographs of Audrey Hepburn.

As a kid, Moore said he dreamed about running away with the circus to be a trapeze artist, and he drew on that inspiration to create some of his final work — a collection of circus pieces for Tiffany in the 1990s. This is the collection (lots 1848 through 1860) that highlights the Sotheby’s auction. Made of sterling silver and enamel, the set includes a Ferris wheel, a carousel, and a giant supporting cast of clowns, elephants, acrobats, lions, horses, animal trainers, and even dinosaurs. [Note: A smaller collection of Moore circus pieces will also be sold at the Christie’s Important American Furniture, Folk Art and Silver auction in New York on January 24.]

Moore retired from Tiffany & Co. in 1994 and died four years later at the age of 88. I apologize for the four billion links I’ve included here, but my GOD the guy was good for a quote. Also, please watch this celebratory video created by one of the lighting companies Moore often worked with. You know you’ve lived one hell of a life when Miss Piggy leaves her sickbed to thank you.

Switching gears, here’s a circa 1880 large Victorian rock crystal pendant that features a central beetle crafted of 18k yellow gold, with a tiger’s eye and pearl body, ruby eyes and legs set with rose-cut diamonds in silver. The rock crystal is suspended from a yellow gold bail with a large bezel-set cabochon garnet.

Cheers to the Mario Buatta: Prince of Interiors auction at Sotheby’s on January 23 for teaching me a new word: “purdonium.” They don’t elaborate on what the hell a purdonium actually IS in the lot details, so further investigation has led me to Michael Quinion’s World Wide Words site, which defines a purdonium as “a trade name for a type of coal-box or coal-scuttle that had a removable metal lining,” that first appeared on the market in 1847 via the London firm of Bell, Massey and Co. It’s all a bit mysterious, but apparently the name is courtesy of a man called Purdon, who may have worked for the company.

This shell-shaped purdonium features decorative tole painting in black and gold, and is in good condition except for some rust on the iron wheels and interior of the shell.

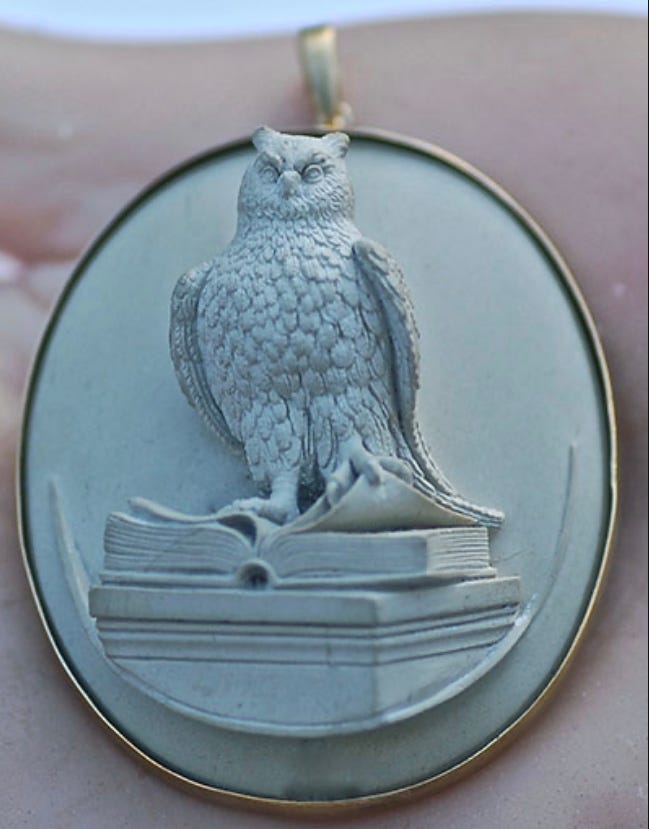

Rowan and Rowan have just posted this brilliant owl pendant, but it’s already sold, *sob.* Circa 1870, it’s carved from lava from the Mount Vesuvius region of Italy, and is extraordinarily detailed — look at those claws lifting the pages of the book! Lava stone is extremely soft, so it lends itself well to high-relief carving, but that also means it’s super easy to break. Lava cameos were very popular Grand Tour souvenirs, but many of the ones that have survived today feature chipped or abraded noses and other appendages, so this unharmed and truly unique piece is a wonderful find.

In a masterpiece of English understatement, the dealer describes the pendant as “rather good,” which reminds me of this passage from the film version of James Clavell’s King Rat:

The California Jewels sale at Bonhams Los Angeles on February 4 will include some pieces from the collection of Hollywood producers Edward and Mildred Lewis, who — over the course of their 73-year marriage — were separately or jointly responsible for such films as Spartacus, Harold and Maude and Missing. The two were avid art collectors, and some of Mildred’s jewelry is featured in the sale, including this Art Deco platinum, amethyst and diamond ring, which is estimated at $600-800.

The Knightsbridge Jewels auction at Bonhams London on February 5 is also loaded with good stuff, but my favorite is this collection of early- to mid-19th century gem-set Halley's Comet brooches. These tiny brooches first appeared on the market after the comet’s 1835 sighting, as a way for jewelers and consumers to capitalize on and celebrate the celestial event. The brooches generally took the same form — comet head followed by the tail streaking behind — but as you can see above, they featured a huge variety of materials and gemstones. Most of the ones above include more affordable materials like seed pearls, pastes and semi-precious stones, but others were made for the upper classes and loaded with diamonds and other precious stones. Some even multitasked — two of the brooches above are also mourning pieces, and feature insets of braided hair.

The brooches became popular again when the comet made its next appearance in 1910, and the designs were a little more streamlined to suit the style of the day.

Ok, that’s all for today, my friends. This one went long! Sorry. Kudos to all those volunteering today, and solidarity to everyone stuck at a computer. As always, feel free to drop me a line by replying to this email, or find me on Twitter @rococopacetic. Have a good week, everyone! xxx

Thanks for reading, and if you haven’t already subscribed, sign up here: