A coral tiara, a historic necklace and an anxious bugbear

And a pretty unsettling Art Nouveau poster, so consider yourselves warned

Happy (morning of) Mischief Night, guys! Somebody once told me they actually call it “Cabbage Night” in New England, which I cannot believe is a thing. Is there anybody up there who can clarify? Drop it in the comments!

If you’ve been here for a bit, you’ll know I usually focus on spooky stuff for this October edition. This time we’re going to wander though some ancient materials and motifs, with a side lesson on a rare type of enameling and a couple “check this out”s that don’t fit the theme but are just too interesting to leave out. At the very least, I hope it’ll provide a few minutes of distraction for those of us in the US who are currently working through a complete nervous breakdown.

Circa 1730, this delicate George II enamel and gold mourning ring features a skull and crossbones with white enamel applied en ronde bosse (“in the round”), which is an enameling technique that was popular during the Renaissance but may date as far back as ancient Crete. It’s a difficult technique; Lang Antique Jewelry University explains the process, which involves applying layers of enamel to a 3-dimensional form in such a way that the enamel won’t just melt off the piece during firing. In order for it to work, a special form of gum must be applied to the metal base that — at an extremely precise temperature — adheres the enamel to the metal and then fires away, leaving no trace. Opaque white enamel was most often used in this technique, and it was thickly applied in a series of layers and fired after each layer. It’s also known as “encrusted enamel,” which unfortunately makes it sound like it’s got barnacles stuck to it.

(I find enameling endlessly fascinating — it’s been around for centuries and as a result there are tons of different types and techniques. If you’re interested, that Lang link above is an excellent place to start.)

Back to the ring itself! The band consists of a series of banner shapes enameled in black and featuring the words “ANN BENNET OB’11 APR:1730 AET 24,” which means it’s a mourning ring for Ann Bennet, who died on April 11, 1730, at age 24. There’s a little compartment on the inside of the ring that contains hairwork — possibly Ann’s, but we can’t know for sure.

The ring is included in the Day Two Wooley & Wallis Fine Jewellery auction on Thursday, and it’s estimated at £1,000 - £1,500, or $1,300 - $1,945 USD.

I feel like I have to show you this wonderful thing, too, even though it’s not spooky:

It’s an early 20th century Fabergé carving of a Gloucester Old Spot pig in dendritic agate. It’s included in Day One (today!) of that Wooley & Wallis auction, and the lot notes mention that, while Fabergé created many popular animal studies, they usually reserved this type of agate for other uses like inlay or panels. In this case, though, they think it was a deliberate choice, meant to mimic the patterns of the Gloucester Old Spot breed of pigs.

Also, I didn’t know about this link between the British royal family and Fabergé:

A number of realistically modelled farm animals including pigs were produced from life at the Sandringham estate in 1907, following a suggestion made to King Edward VII by Fabergé’s London agent Henry Bainbridge that the firm recreate a number of the animals across the estate. With subjects ranging from the King's own terrier dog Caesar, to the cows, pigs, ducks and chickens that populated the farmland around them, the animals of this ‘Sandringham Commission’ were reproduced in wax sculptures by the carver Boris Frödman-Cluzel, before being sent back to the Russian workshops to be immortalised in hardstone. They were then sent back to Fabergé's London branch for purchase, mostly, but not exclusively, by those who wished to gift them back to the Royal Family. Such was the appeal that some were even acquired by members of the family themselves, such as Princess Victoria, who bought a model of a recumbent white sow in pale pink aventurine quartz in 1912.

Wooley & Wallis don’t know if this piggie was part of that commission, but they do note that “King Edward VII was particularly proud of his pigs,” which (charmingly) makes him sound like Lord Emsworth and the Empress of Blandings. It’s estimated at £5,000 - £7,000 ($6,500 - $9,000).

Circa 1860, this tiara comb features polished branches of red coral set on a tortoiseshell comb. The dealer, London’s Rowan and Rowan, refer to it as a “crown of thorns” comb, in reference to the wreath of thorns described in the New Testament as being set on the head of Jesus by his captors.

According to the GIA, humans have been wearing coral for 30,000 years, and of course in that time it’s become associated with a whole host of myths and superstitions: it was formed from the blood of Medusa, it quiets the oceans, it protects babies, it wards off evil spirits and brings all good things to its wearer. The comb above dates to a particularly popular time in its history, as coral was all the rage in 19th-century London. It was harvested from the waters near Naples, Italy and carved and polished by local artisans for the London market, and according to the Victoria & Albert Museum, the jewelers Phillips Brothers were the main supplier of coral goods in London — to the extent that Robert Phillips “received the order of the Crown of Italy for his services to the coral industry in Naples.”

It looks like the comb above was actually retailed by the London crown jewelers Garrard & Co., because it still has its original fitted case. I usually love coral tiaras but this one is a bit too…..I don’t know, fleshy? squirmy? for me. Here’s a Phillips Brothers tiara in the V&A; it’s a little more structured and includes round polished coral beads that mimic berries.

If you have some evil spirits to banish, Rowan and Rowan are selling the comb for £2,200, or $2,900 USD.

As soon as I heard that Bonhams Los Angeles was holding an online auction titled Elegance of the Eternal: The Anne Rice Collection, I tripped over myself to get to the website. Anne Rice! That’s gotta be some good stuff! Well folks, let me tell you: there is SO. MUCH. FLATWARE. I’m not kidding — like, a bananas amount of flatware.

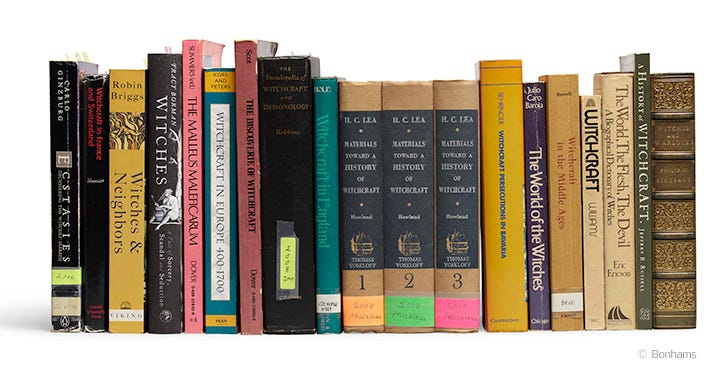

But if you continue scrolling you’re eventually rewarded with her book collection, which includes some tempting annotated copies, including her own Interview With The Vampire and other famous works like The Godfather and Gone With The Wind. There’s also a selection of themed groupings of books from her personal library, and I think if I were going to try for something, it would be this collection of 18 books on witchcraft. I won’t, though, because while Bonhams estimated the group at $200 - $300 USD, the current bid is $3,800. The sale ends tomorrow. Ah well.

The website of New Orleans antique dealers M.S. Rau is always worth a root, because you never know when something like this ca. 1780 French gunpowder flask might pop up. The flask is made of coconut shell and is hand-carved with scenes of burglars and a distressed maiden, but the end of the shell depicts a formidable legendary beast called a “bugbear.”

I always love stumbling across a new monster, especially one that originated in English folklore. Some Dungeons & Dragons or My Little Pony (!?) fans may already be familiar with bugbears, but they’re a type of hobgoblin invented to frighten misbehaving children. The term dates back to the 1500s, and according to Merriam Webster, the “bug” in bugbear:

refers not to an insect, but instead comes from the Middle English word bugge. This bugge was used for all kinds of imaginary spooky creatures — from ghosts and goblins to scarecrows—that cause fright or dread. In the 1500s this bug was combined with bear (as in the animal) to form bugbear, even though there is little evidence that either a bug or bugbear took an ursine form. In fact, based on its earliest known uses, bugbear began as an all-purpose word for things that cause fear or dread, not just supernatural beasties.

This particular bugbear — who, to be honest, looks a little too anxious to be scary — features glass eyes and a stopper “mouth” that’s attached by a chain to a lug on the side of the piece. M.S. Rau says flasks of this sort may have been carved by soldiers or sailors passing through the East or West Indies, and possibly also by French prisoners of war. They’re selling it for $8,850, so obviously Mr. Bugbear will be staying in New Orleans for the time being.

Also, side note: don’t miss this incredible ca. 1810 model of a guillotine carved by a French prisoner during the Napoleonic Wars. I told you M.S. Rau has cool stuff.

Holy hell. This poster is by Henri Privat-Livemont (1861-1936), a Belgian Art Nouveau painter and poster artist. The piece, which is titled La réforme le 21 Novembre. Le masque Anarchiste, 1897 (“The Reform on November 21, the Anarchist Mask”) is up for sale in the November 7th Symbolist Sale at Bonhams Brussels, Chaussée de Charleroi.

It’s clearly an upsetting and violent image, and all Bonhams has to say is:

"La Réforme" features a striking and controversial image depicting Livemont's first wife in a moment of violence, reflecting both personal turmoil and social commentary. This powerful work showcases his ability to blend beauty with darker themes.

Hey thanks.

I haven’t found anything that confirms this yet, but the date of the poster and the word “Montjuich” make me think this poster is a reaction to the Montjuïc trial in Barcelona, which, according to Wikipedia, led to the execution of anarchist supporters and “a severe repression of the struggle for workers’ rights. During this era, ‘Montjuïc’ was synonymous with barbarism based on the torture of anarchists and others imprisoned there.”

I can’t find much about the poster itself, although it’s available on page after page of art reproduction sites. One of those sites does contribute a little more on the subject, calling it an “exploration of political tone and societal turmoil at the turn of the 20th century,” as political activism and the anarchist movement began to unfold in Europe. And clearly there is a lot going on here, as, aside from the horrific central scene, other figures lie seemingly dead in the background and a series of battle-scarred and bloody (Anarchiste?) masks are skewered on a sword on the right, devolving into a skull at the bottom. Is this a comment on political extremes and the dehumanization that inevitably follows? Wow, sounds familiar.

It’s unsettling how arresting and even beautiful the composition is, though, with the dark, stylized trees in the background contrasting with the lettering, and the decorative floral panel framing the masks. Even when it’s grim, Art Nouveau is still extremely seductive.

The poster is estimated at €3,000 - €5,000, or $3,300 - $5,400 USD.

This jet mourning parure dates to the late 18th to early 19th century. A parure is a set of various pieces of matching jewelry, and this one contains a necklace with three detachable pendants, a set of earrings, a brooch, a “jewel” (which, after peering at the photo of the back, I think may be a brooch or clip that has lost its pin), and two black velvet bracelets embellished with jet rosettes. The set isn’t all that pretty in the photographs, but it was probably gorgeous and glittery in low light.

Jet is often associated with mourning because of its extensive use in the 19th century. After Prince Albert’s death in 1861, Queen Victoria went into deep mourning and pulled England along with her, demanding that only jet jewelry be worn at court. So while everybody still dressed up, they had to do it all in black (or, in later stages, gray or purple). Many strict rules on mourning etiquette and fashion evolved in England, Europe and the US — this 1857 edition of Godey’s Magazine observes that “In Philadelphia, severity and newness carry the day; in New York, many do not scruple to mingle jets and bugles, crape flowers and feathers, even in what they call deep mourning.” Bugle beads and feathers in mourning!? With these spartan Quaker roots??? Philadelphians would NEVER.

Anyway, jet — which is actually fossilized wood from the Jurassic period — evolved into a popular option for mourning jewelry because it was both very lightweight and very black in color, and much of it was sourced in Whitby, England (of Dracula fame). It was also often faked, with pretenders including vulcanite (vulcanized rubber invented by Charles Goodyear), French jet (black glass), gutta percha (another form of rubber sourced from the tropics), horn, onyx and even — in the early 1900s — bakelite.

It’s important to note that not all jet jewelry was mourning-related, though — black was a stylish color in the late 1800s, and many jet pieces were prized simply for their look.

This parure, which was formerly the property of the Ducal House of Bavaria, is included in the Sotheby’s Royal & Noble Jewels auction in Geneva on November 13. It’s estimated at 500 - 900 CHF (Swiss francs), or $578 - $1,000 USD.

Speaking of that Royal and Noble auction, I also have to mention the sale’s showstopper: an extraordinary 18th century jewel that is estimated to fetch between $1.8 million and $2.5 million.

The piece — which is set with nearly 500 diamonds weighing a total of approximately 300 carats (!!) — is referred to as a négligé, and is basically an open-ended rope consisting of three rows of collet-set old cushion-shaped and circular-cut diamonds, with each end capped by a hefty diamond tassel. It’s extremely flexible — it “courses through one’s hand like running water,” to quote a Sotheby’s chairman — and can be worn loose around the neck or draped over itself like a scarf.

It’s extraordinary that this piece (with SO MANY DIAMONDS) has made it this far without being broken up. And the diamonds themselves are also extraordinary: Sotheby’s notes that diamonds weren’t widespread until their discovery in South Africa in 1867, so the only diamonds available in the 18th century came from the fabled Golconda mines in India, which produced some of the purest and finest diamonds in history. They were so rare and so expensive that only royalty and the highest echelons of society could afford them.

The exact origins of the jewel aren’t known, although there is some titillating speculation in the lot notes suggesting that the tassels came from Marie Antoinette’s infamous diamond necklace. We do know that it resided for generations in the collection of the British aristocratic Paget family, and probably first was acquired around the time of Henry Paget (1768-1854), the first Marquess of Angelsey. Because it was part of the family estate, it luckily avoided being sold off during the bankruptcy of the 5th Marquess of Anglesey — who my longtime readers may remember as “The Dancing Marquess,” a.k.a. that guy with the emerald ping-pong jacket.

The piece later witnessed two coronations: the 6th Marchioness, Marjorie Paget, wore it to the coronation of King George IV in 1937, and the 7th, Shirley Paget, wore it draped like a scarf to the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953.

The Pagets parted ways with the piece sometime in the 1960s. It later resurfaced in a 1976 Bicentennial exhibition at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and then moved on to “an important Asian private collection” in the 1970s, where it has remained until today.

Ok that’s it. Solidarity, my friends, and Happy Halloween. M x

Oy! The joy of your posts! Your Canadian friends are pulling for you at this time of pure crazy. Love wins Pet. You're precious to us, and we send you love and light.

I'm from Bergen county NJ and we ABSOLUTELY called it Cabbage Night! It wasn't until college that I realized most folks called it Mischief Night, and really it was primarily a small pocket of north Jersey (like six towns) that called it Cabbage Night