An astrolabe, a Venetian traveling case and a Faberge baboon

Scroll to the end for a link to the auction with all the dog paintings

Hi everyone! I was delighted to unearth some old and interesting things for this edition of the newsletter; I hope you enjoy.

I feel like this is the kind of thing I used to see on QVC, except guess what? It’s from 1790. This cardboard slipcase comes from Germany, and contains three trays (one of them is empty) of thirty-six cabochon oval specimen hardstones with a central gold ring that has a hinged back, so the stones can be swapped in and out to match one’s outfit. (I regret to tell you I am too old to use the term “fit.”) The set is attributed to the workshop of goldsmith Johann Christian Neuber, Court Jeweler to Frederick Augustus III of Saxony in Dresden.

It’s in the Classic Design: Furniture, Silver & Ceramics auction at Sotheby’s New York later today. It’s estimated at $10,000 - $20,000, but as of right now it’s up to $32,000.

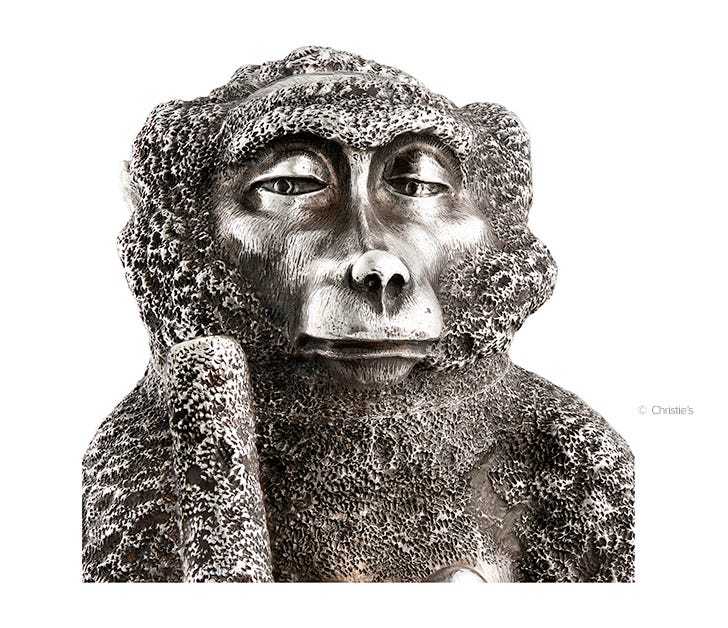

Circa 1908, this extremely mellow silver Fabergé baboon is actually a lighter. (His head flips up to reveal the compartment for lighter fluid.) He’s very finely modeled, with heavy surface chasing to mimic thick fur, and he’s sitting on a detachable stone base that is a later addition.

In addition to the Fabergé and Imperial marks, he also features the hallmark of the First Silver Artel, a collective of silver and gold artisans who were working in St. Petersburg in the early 1900s. Dr. Géza von Habsburg’s book Fabergé: Imperial Craftsman and his World notes that the group came into existence when Julius Rappoport, a Fabergé silversmith renowned for his silver animal figurines, decided to retire in 1908. Rappoport left his workshop and equipment to his workmen in gratitude for their years of service, and their group became known as the First Silver (or Silversmith’s) Artel. (According to Pushkin Antiques, there were actually 34 different artels for silver, but little is known about most of them.) The House of Fabergé supported the collective and sent them commissions, but von Habsburg says that “after two or three years of internal discord, increases in the cost of production and decline in its quality, the Artel ceased to exist.” It folded probably around 1912 or 1913.

Anyway, I’m highlighting him just for this image because my man is a whole mood.

He’s included in the Christie’s online auction The Collector: London closing on April 23, and he’s got an estimate of £4,000 - £6,000 ($5,000 - $7,500).

I’m also compelled to point out this utterly batshit late 19th century French porcelain and gilt-brass carriage clock that looks like it’ll start spinning its pillars and playing carnival music two beats after you walk past it. (And then stop when you look back.)

It’s signed “LUCIEN PARIS” and is also included in that Collector: London auction, estimated at £1,200 - £1,800 ($1,500 - $2,200).

On April 24th, Bonhams is holding an Important Instruments of Science and Technology auction in London. Please look through it — the lots are incredible, although they will make you weep for the beauty and skill humans once exhibited in the creation of everyday objects. But hell, I’m sure developing large language models that use more energy than tens of thousands of US households to generate an anime waifu with huge tits is cool, too.

Anyway. The most important lot in the auction is the Regiomontanus/Cardinal Bessarion astrolabe above. Made of brass and dated 1462, it’s inscribed (in Latin) “Under the protection of the divine Bessarion on whom all can be said to depend I arise in Rome the work of John 1462.”

The astrolabe was created by a young German humanist, Johann Müller (1436-76) — later known as Regiomontanus — under the patronage of Greek Cardinal Johannes Bessarion (1403-1472), another humanist and scholar who advocated for the reunification of the Greek and Roman churches. The astrolabe was one of Müller’s early works, and its design is transitional, featuring engraved Roman script characteristic of the 1400s as well as traces of the preceding Gothic style in some of its numerals and the use of a quatrefoil motif.

Astrolabes were a common tool for centuries. Laura Poppick’s article “Heavens Above” for Bonhams notes that the first astrolabe appeared in the Roman Empire “around the 2nd century AD, and spread to the Islamic world by the 8th century. They remained in use up until the 17th and 18th centuries.”

Their purpose was to track the stars and map one’s location, but they also were used in the Middle Ages for zodiac-based decision-making (we just can’t help ourselves when it comes to astrology, can we?). To use one, Poppick says:

you might first begin by looking through a pinhole on the back of the instrument to find a familiar star in the night sky. From there, you could determine the star’s altitude and carry on with additional calculations on the front of the device, where a round plate with a two-dimensional projection of Earth’s latitudinal lines sat layered with other rotating features. Because the position of stars shifts depending on the geographic location from which you view them, astrolabes often came with a collection of several different plates, each representative of the latitude of a different major city.

The Regiomontanus astrolabe marks the position of 30 named stars that are listed in the lot notes. It also has three interchangeable plates, one of which is marked for Rome.

Further engravings on the back of the piece include a degree scale in four quadrants, “to allow readings to be taken in both altitude and zenith distance,” as well as a zodiacal calendar and the Latin inscription mentioned above. An engraved angel overlooks it all.

If you’re interested in going down a major rabbit hole, historian and author David King wrote a book about this piece called Astrolabes and Angels, Epigrams and Enigmas: From Regiomontanus' Acrostic for Cardinal Bessarion to Piero della Francesca's Flagellation of Christ. King believes that the letters in the astrolabe’s inscription can be isolated into various groupings that identify the figures in the painting The Flagellation of Christ by Piero della Francesca. You can download a pdf of his book here.

The astrolabe is estimated to sell for between £250,000 - £350,000 ($310,000 - $440,000). It’ll be an interesting one to watch.

Circa 1880, this four-strand seed pearl, enamel, tourmaline and diamond necklace was made by Carlo Giuliano, one of my all-time favorite jewelers.

Giuliano was an Italian goldsmith who moved to London in the 1860s. According to Geoffrey Munn’s book Castellani and Giuliano, Revivalist Jewellers of the 19th Century, it’s believed he originally worked for the famous Castellani family of jewelers in Naples, and moved to London to open a branch for them. He later started his own successful shop, specializing in Renaissance Revival and archaeological-style jewelry.

Giuliano was best known for creating intricate pieces that paired gemstones with enameling in the “Holbeinesque” style (named after the Renaissance artist Hans Holbein), which surrounded a central gemstone — in this case, a green tourmaline — with a scrolling openwork frame covered in tiny sections of black and white enamel alongside diamonds and pearls. I can’t resist showing you the detail:

Carlo died in 1895, but his two sons, Carlo Joseph and Arthur, continued the business until the start of the First World War. Their work is very similar to their father’s, but unfortunately, the Giuliano firm ended sadly. We don’t know when Carlo Joseph died, but Arthur committed suicide in August 1914. His motives aren’t known, but according to Munn’s book he had recently left his wife of 20 years for another woman, and it also can’t have been easy to maintain a luxury business after the outbreak of World War I. The business closed after his death, and any remaining stock was sold at auction.

The necklace is included in the Paris Jewels - Bonhams live auction on April 25 and is estimated at €10,000 - €15,000 ($11,000 - $16,000).

LOOK AT THIIIIISSSSS. It’s a *deep breath* North Italian leather-bound black and gilt-decorated hardstone and mother-of-pearl inlaid traveling cabinet.

Christie’s says that small cabinets like this, which were used for traveling and storing precious items, were a staple in Europe. This one was “most probably conceived in the lacquer workshops of Venice in the late 16th or early 17th century,” and different preferences in cabinet inlay evolved across different areas of Europe — so while hardstones were popular in Rome, pietra dura, or marble marquetry, was all the rage in Florence, and the Spanish preferred ivory, bone and shell.

The architectural design of this particular cabinet also features inlay that’s been cut into ovals and squares in a nod to the facades of Venetian palazzi. The leather case was decorated probably in the 17th century, and the cabinet includes samples of mother-of-pearl, lapis lazuli, lumachella — a.k.a. “fire marble,” an iridescent marble composed of fossilized snail shells — and agate. Christie’s think the wooden pillars are later replacements for originals made of hardstone.

The cabinet is included in the Christie’s The Collector: New York online auction ending on April 25. It’s estimated at $7,000 - $10,000.

This is not my usual kind of thing, but I love this Art Deco necklace made of red and white glass panels — click the link to see another photo that shows how, when it’s worn, the placement of the red panels make the color seem like its being pulled down by gravity and pooling at the bottom of each segment. Gorgeous. It’s currently up on Butter Lane’s website for $950. Somebody get it.

One final note just for funsies: tomorrow’s European Art and Old Masters auction at Freeman’s | Hindman has a ton of delightful 19th century paintings of dogs — look at this little guy who is Thinking Big Thoughts about whatever he just read, and this Pom who, be warned, will gaze directly into your soul. A jewelry-adjacent piece is this miniature painting of Venice (complete with tiny easel) by Duke Fulco di Verdura. (Yes, that Verdura.) I love the little trompe l'oeil frame he painted on the back.

Ok, that’s it for tonight. Enjoy the rest of your week! Love, M xx

I'm so glad you all enjoyed this one! I did, too. It felt like the old days, when there seemed to be more interesting, old and unusual things around. Lately it seems like I spend hours scrolling through auction after auction and they all have the exact same big, Retro mid-century yellow gold jewelry that everybody else has. It's a drag. How many Van Cleef & Arpels Alhambra necklaces does the world need? A LOT FEWER

I love EVERYTHING in this one! The monkey's face, the Guiliano necklace, THE BOX, the carriage clock (which looks like your logo made by a dyslexic Victorian) and the astrolabe which makes me think that our race has lost a step or two in the brain department over the last few centuries. Thanks for making my morning!