Darwin’s microscope, Josephine’s diadem and a Lalique collar

I want every single thing in this newsletter.

Hi everyone! I hope you’re all well. I’m actually feeling a bit fragile, thanks to some nefarious asshat who used last week’s newsletter to spoof my Dearest email address. I woke up to an inbox full of strangers yelling at me to stop spamming them with surveys from Best Buy. Some were even in German! Turns out German shouting sounds even angrier in print than it does in person; who knew. Anyway, Substack is on the case, although I don’t think there’s much they can do about it. I’ll certainly be hitting “publish” with much trepidation this time around. Wish me luck!

Before I get started, I have an update: remember that Louis Comfort Tiffany Medusa pendant/necklace from last week? After an almost 10-minute bidding war involving three participants, the piece finally sold for $3.65 million. It set a new auction record for a piece by L. C. Tiffany and absolutely ethered its original $100-200k estimate.

Now, the ca. 1805 carnelian, enamel and gold diadem you see above is the one I couldn’t fit into my previous newsletter. It also sold last week — in the December 7th Treasures auction at Sotheby’s London — for a measly £450,600 (around $598k). It beat its estimate by £150k, but still, that’s quite a bargain compared with that Tiffany price. Especially since it belonged to Joséphine Bonaparte, the Empress of France.

The piece is part of a set (or parure), consisting of the diadem, a pair of earrings, a hair comb and a belt ornament. They all feature carnelian intaglios that were a gift to Joséphine from Napoleon’s younger sister Caroline, who, as Queen of Naples, was a patron of the excavations in Pompeii and owner of a large collection of antique gems as well as newer pieces by contemporary artisans.

The fascination with and heavy promotion of classical motifs was key to Bonaparte’s reign because, as Sotheby’s notes, he and Caroline “knew how effective associations with classical symbolism were in terms of legitimising an un-inherited claim to power.” Without being born into royalty, Napoleon had to establish and promote his rule some other way, basically relying on neoclassical propaganda to present himself as a strong and fair ruler. He bombarded the public with images depicting himself as a Roman emperor, complete with laurel leaves and drapery and a strong muscular build.

Joséphine helped, modeling her clothing and jewels — and even her hairstyle — on those worn by women of Greek and Roman antiquity. She, like Caroline, had a huge collection of antique and contemporary engraved gems, including many cameos and intaglios that had been excavated from Herculaneum and Pompeii. Some she displayed in cases, while others she had mounted into jewelry, and according to historian Diana Scarisbrick, imperial jeweler Marie-Étienne Nitot created a real doozy of a pearl parure for Joséphine in 1808. It incorporated 45 cameos and 36 intaglios into the design and was so stinking heavy there’s no record of her ever actually wearing it. But still, she loved her jewels:

“Josephine’s greatest pleasure when at Malmaison was to sit at a table with her ladies beside a fire, and show them the cameos she was wearing that day. Then she would call for the boxes containing the rest of the collection to be brought so that every piece could be examined.”

It also didn’t hurt that this simpler, idealized vision of antiquity was a complete about-face from the over-the-top bananas Baroque and Rococo styles of the previous century. Society loved it and engraved gems became hugely popular, particularly as they were “believed to endow the wearer with their various depicted qualities such as heroism, faithfulness and love.”

This parure is a wonderful example of the style. (Note: There were a few additional items from Joséphine’s collection in the sale, including this second, smaller parure and a ca. 1810 French or Italian choker that I would cut you for.) The diadem features a central band of interlocking circles with blue champlevé enameling that is entwined by a wider enameled ribbon of scroll and foliate motifs. The ribbon is set with 25 carnelian intaglios — some of which may be ancient — and most feature classical carvings of male or female heads. Both parures bear the hallmark of French goldsmith Jacques-Ambroise Oliveras, who was known for his skill in mounting engraved gems in gold and enamel.

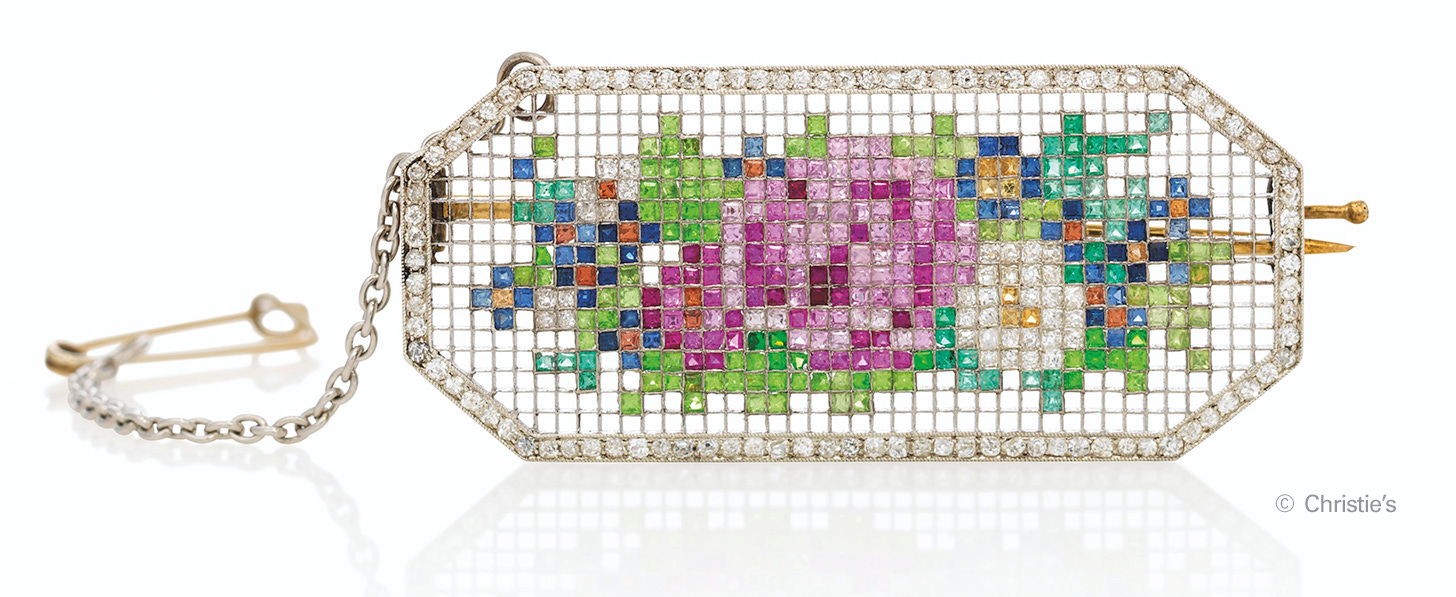

I couldn’t fit this piece into last week’s post, either, but it definitely still deserves a mention. This lovely ca. 1913 gold and platinum mosaic brooch by Fabergé was the highest-selling lot in the A Selection of Fabergé Masterpieces from the Harry Woolf Collection at Christie’s London on November 29, probably due to its rarity and resemblance to the 1914 Fabergé Imperial Mosaic Egg. This brooch and the egg are the only two known existing examples of this Fabergé mosaic style.

The style was the brainchild of Alma Pihl, a young woman with strong familial ties within the Fabergé firm — her father was Oscar Pihl, head of the Fabergé jewelry workshop in Moscow, and her mother was the daughter of famed workmaster August Holmström. Alma started to work for her uncle Albert Holmström (who had taken over August’s workshop after his death in 1903) when she was 20, making watercolor copies of current Fabergé designs for the company archives. In her spare time, she would sketch her own designs.

Those sketches were GOOD, and her uncle’s skill in bringing them to life resulted in some of the most gorgeous objects — the Mosaic Egg, the Winter Egg and the Nobel Ice Egg (my favorite, even though it’s not Imperial) — to emerge from the Fabergé workshops. It wasn’t easy, though. Christie’s notes that the mosaic technique:

“required the most skillful jewellers, as each miniature stone had to be calibré-cut in such a way that it would perfectly fit into the square holes of the platinum mesh, which was also cut by hand.”

The brooch, which depicts a bouquet of flowers in a mosaic style that resembles embroidery, consists of a platinum trellis-work panel set with diamonds, rubies, topaz, sapphires, demantoids, garnets and emeralds. It sold for £350,000 ($464k), well above the estimate of £70 - 90k ($93-119k).

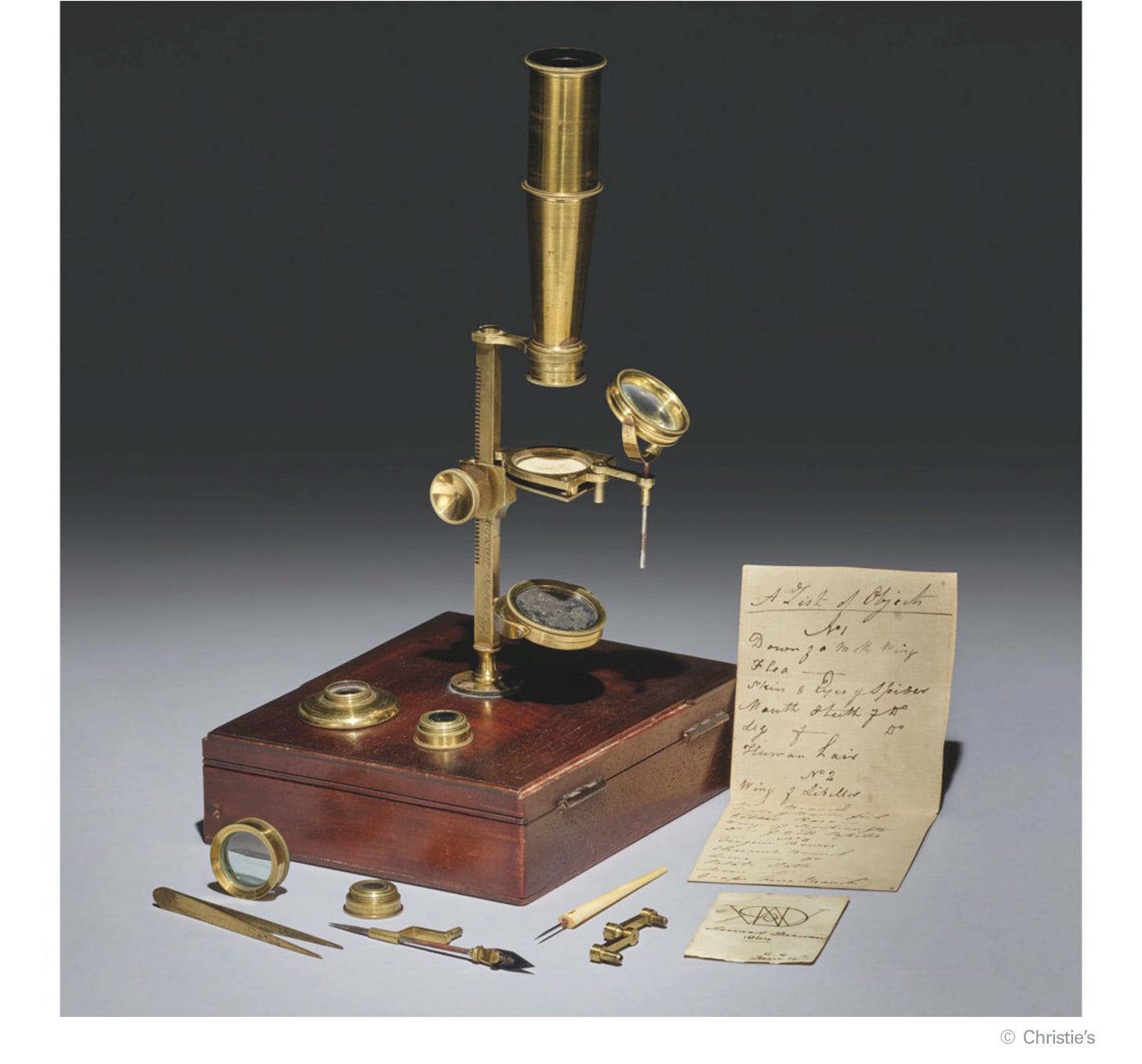

Moving on to some upcoming sales, this ca. 1826-1830 small lacquered brass microscope will be included in the Christie’s London Valuable Books and Manuscripts auction on Wednesday.

This piece is a type of “pocket” microscope that was designed by Charles Gould for the London firm Cary around 1825. It completely disassembles, so it can fit into that small 5 1/3” wide box.

The thing that sets this particular microscope apart, however, is that it belonged to Charles Darwin. More specifically, “it is one of only six surviving microscopes known to have belonged to him, and the first ever to come to auction.” So, kind of a big deal! It’s estimated at £250,000 – £350,000 (around $332 – 464k).

Christie’s speculates that Darwin may have used it in his early, pre-Beagle study of sea creatures pulled from the Firth of Forth “while he was trying to avoid his medical studies at the University of Edinburgh,” lol. They note that, of the five other microscopes Darwin is known to have owned, two of them were bought after this one, and the others aren’t suitable for studying marine invertebrates.

Charles handed the microscope down to his son Leonard (the lot also includes a monogram of Leonard’s from 1864) and it’s been in the family ever since. Christie’s quotes an extremely sweet excerpt from a letter Charles wrote to his eldest son William in 1858:

‘Lenny was dissecting under my microscope & he turned round very gravely & said “dont you think, papa, that I shall be very glad of this all my future life”.—’

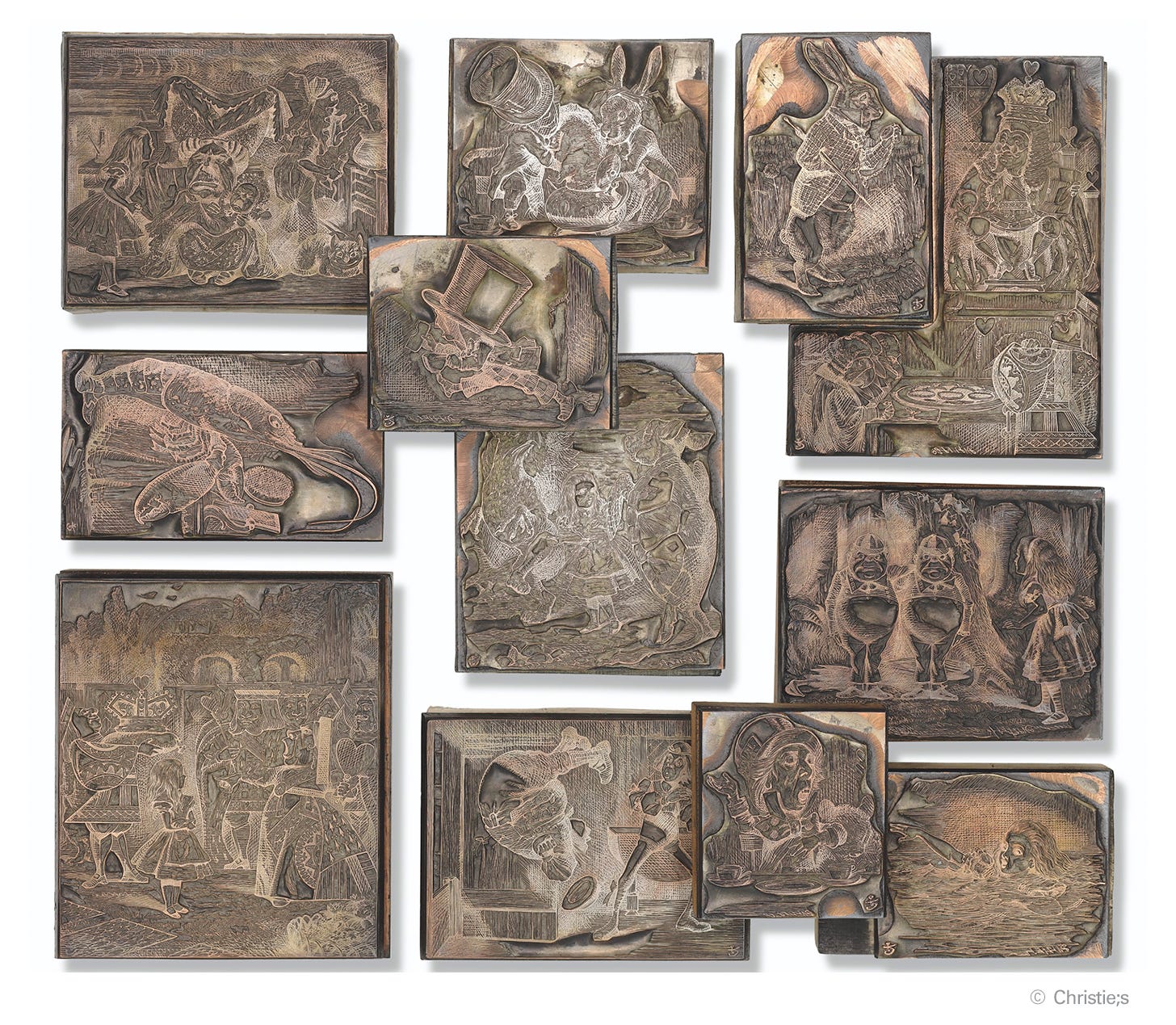

Another lot that caught my eye in that Wednesday sale is this collection of original printing plates featuring John Tenniel’s illustrations for Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

According to Christie’s:

The first edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was printed by The Clarendon Press for Macmillan in 1865 using these blocks. However, when Tenniel saw the first copies, he was not pleased with the reproduction of his illustrations, and persuaded Dodgson to recall all the copies that had been printed (R.L. Green, ed., The Diaries. London, 1953, p.234). Only about 20 copies of that first edition survive; it is one of the rarest and most valuable books in English literature.

The lot consists of 12 copper-plated lead printing blocks mounted on wood. Eleven feature illustrations for Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, and the twelfth is an illustration for the first edition of Through the Looking-Glass, and what Alice found there.

More intaglios! This ca. 1870 gold, hardstone intaglio and garnet bead necklace is by Castellani, a 19th century multigenerational family firm that was the first powerhouse of archaeological revival jewelry.

In 1814, Fortunato Pio Castellani opened his first shop in Rome. In addition to being a skilled jeweler, Fortunato was an avid amateur archaeologist, and he was invited to observe and comment on some jewels recently unearthed from an Etruscan tomb in Cervetri, near Rome. He was fascinated by the ancient pieces, and immediately began to explore and try to recreate the elaborate goldsmithing techniques used by the Etruscan craftsmen. He was pretty darned successful — although neither he nor his descendants could ever crack the science behind granulation — and his designs were a major driver of the archeological jewelry craze that remained popular throughout the 19th century.

Like Josephine’s parures, the Castellani style incorporated both ancient and modern engraved gems and elaborate gold work, and they’re also credited with being the first to add micromosaics into the mix (check out this Medusa brooch at the Met). The necklace above showcases 14 brightly colored intaglios in an elaborate gold collar made up of stylized scroll and cylinder links. The edges are lined with 56 garnet beads. And even better, the piece can be detached and worn as a set of bracelets! It’s included in the Doyle Important Jewelry auction on Thursday in New York.

Fortunato’s sons Alessandro and Augusto eventually joined him in the business and the firm expanded to branches in Paris and London. Alessandro actually helped the French government with the purchase of a large collection of ancient jewelry, but in an attempt to keep other antiquities within the country, the family created its own collection and established a gallery where people could view ancient jewelry alongside their own 19th century replicas.

Augusto’s son Alfredo steered the jewelry firm into a successful third generation, but the company ended with him. Tastes had changed and he had no heirs, so the writing was on the wall. He preserved the family’s collection by giving it away to various museums, with the bulk of it going to the National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia in Rome, where you can still see it today.

There’s so much to the Castellani story — particularly Alessandro, who was a one-handed (hunting accident) Man of Strong Opinions who lectured all over the world about the glories of ancient craftsmanship and occasionally had to skip town due to political strife and/or personal indiscretions — and I’ve left sooo much out. I wrote about the family back in the day for JCK, but unfortunately it’s now behind a prohibitively expensive paywall. If you can find a copy, I highly recommend Geoffrey Munn’s Castellani and Giuliano: Revivalist Jewellers of the Nineteenth Century. Munn is the former managing director of Wartski and a very familiar face from the BBC Antiques Roadshow.

This tiny English spyglass/etui (a small ornamental case for holding needles and other household implements) will be offered in the Christie’s London Two Private Collections of European Ceramics, Gold Boxes and Silver auction on Thursday.

Ca. 1790, the piece is made of glass and enameled to resemble blue agate, with pierced and chased gold mounts featuring scrolls, columns and garlands of flowers. A band of opaque white enamel circles the rim, with the words “L'amitié vous l'offre,” which I think means something like “friendship offered to you.” (I took Italian! Sorry!)

This piece doesn’t contain any tools, but it’s very similar to this earlier ca. 1760 telescope/etui that sold at Sotheby’s last May. That one held a pair of scissors, a tweezer, a miniature sabre and a pencil holder inside.

On December 17, Sotheby’s Paris will present Claude H. Sorbac: la collection d’une vie, René Lalique. Sorbac was a French entrepreneur, businessman and Art Nouveau collector. He had a particular fondness for the work of Lalique that led to him eventually becoming an expert on the subject.

The ca. 1906-1908 “Loving Swallows” horn and diamond comb above features two overlapping birds, one of which holds a delicate branch of 18k gold and diamonds in its beak. Two wings — one from each bird — extend down to form the tines of the comb. It’s a wonderfully elegant example of Lalique’s work.

The piece is estimated at €400 – 600k, or $453 - 679k.

The thing I REALLY love in this auction, though, is this ca. 1909 Lalique “Chantecler” collar. Made of openwork leather cut into a rooster motif, the piece is heavily embroidered with silk and accented with glass berries and white enamel and 18k gold. The clasp is set with a cabochon citrine.

PLEASE click through and blow up the images; the detail is amazing.

Other interesting auctions coming up:

Books and Manuscripts Online and Fine Books and Manuscripts at Bonhams New York, December 15: HUGE collection of Pre-Raphaelite letters and other ephemera.

Tea Treasures – Rare Vintage and Premium Puerh | The Inaugural Tea Sale, Sotheby’s Hong Kong, December 16: Very old tea selling for thousands of dollars? Great, now I need to try it. Stupid Sotheby’s.

I think that might be it for this year, my friends. There’s not much happening after this week, but if something amazing pops up I’ll be sure to send out an alert. I hope you’ve enjoyed these recaps and pray I haven’t taxed your patience too much with this one (I did go on a bit; sorry). And thank you, as always, for your kind words and shared enthusiasm.

I hope you all keep safe and get some rest over the holidays, and if you get a Best Buy spam email from me, please don’t yell at me in German.

Cheers! M xxx

Good lord the Chantecler collar

Darwin studied eels! An enduringly mysterious creature. I read of it in the Book of Eels.