Hi all. This lovely bracelet isn’t the most expensive lot in today’s Magnificent Jewels and Noble Jewels auction at Sotheby’s Geneva, but it’s certainly the prettiest? Entitled the “Birds in Flight” bracelet, it dates to circa 1927 and was created by the famed New York jewelry manufacturers Oscar Heyman & Brothers for Shreve, Crump & Low, one of the oldest jewelers in America.

A masterpiece of Art Deco design, the bracelet is articulated and features a swirling pattern of tropical birds in flight against a floral background, with buff top rubies, emeralds, sapphires and onyx providing vibrant flashes of color alongside circular-cut diamonds. Each stone was cut, set and polished in the Oscar Heyman workshop, and, in total, the bracelet took over 1,500 hours to complete. It carries an estimate of $473,361 – $750,328.

Known as the “jewelers’ jeweler” because they’ve spent decades creating pieces for some of the biggest jewelry houses — Cartier, Tiffany & Co., Black, Starr & Frost, Van Cleef & Arpels, etc. etc. etc. — the Heyman company’s story began in 1906 when Latvian teenagers Oscar and Nathan Heyman fled Eastern Europe for New York City. The brothers were training as jewelers and had done work for Fabergé, but they were Jewish, and their religion made them targets amid the fierce anti-Semitism of the Russian Empire in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

“They had to leave Russia,” second-generation family business member and current president of the firm Adam Heyman told Family Business magazine. “Their parents said, ‘Take your Fabergé skills to New York City,’” and they did, with seven more brothers and sisters — and their parents — later making their way to the city to join them. Eight of the nine total siblings would eventually work at the firm they formally established in 1912.

The brothers began by working for other companies — their timeline notes that Oscar was the first non-French jeweler hired by Pierre Cartier — and their skills were in high demand because were already experienced in working with platinum before they arrived in New York. Each brother brought a skill to the business, and even today, a big part of the Oscar Heyman success is due to their one-stop-shop expertise across all facets (heh) of jewelry-making — alloying metals, stone cutting, setting, engraving, design, etc. The company quickly stacked up patents for innovative new hinges and tools, and in 1939, they developed the famous “invisible setting” technique for Van Cleef & Arpels.

The firm pivoted during World War II and began producing precision mechanisms for things like clocks and airplane instruments, but they did continue to make a small amount of jewelry items with patriotic themes. Some later standout moments occurred in 1969, when they feverishly designed and created a necklace for the Taylor-Burton Diamond (Cartier gave them a one-week deadline, because Liz wanted to wear it to a ball), and in 2012 — their 100th anniversary year — when their 6.54 ct. pink diamond ring from the collection of Evelyn H. Lauder sold for $8.59 million at Sotheby’s.

The firm is still going strong today, with members of the second and third generations at the helm. If you’re interested in learning more, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston published a terrific book, Oscar Heyman: The Jewelers’ Jeweler, in 2017.

There are a couple of huge diamonds in the Christie’s Magnificent Jewels auction taking place tomorrow in Geneva. The larger of the two is a 228.31 ct. pear-shaped, colorless diamond called “The Rock” that they claim is the largest white diamond ever to come to auction (I honestly don’t care enough to research this; sorry). It could sell for as much as $30 million and was mined in South Africa around 20 years ago. Eh.

The OTHER huge stone (above) is the Red Cross diamond, a 205.07 ct. fancy intense yellow cushion-shaped diamond, with a pavilion faceted in the shape of a Maltese cross. The rough stone — which weighed between 370 and 380 carats — was first unearthed in 1901 in the De Beers-owned Grinqualand mines in South Africa.

This isn’t the first time Christie’s has seen this diamond.

During the First World War years of 1915 through 1918, Christie’s organized a series of annual sales to benefit the work of the Red Cross. The auctions were held over the course of 10 to 15 days and included a range of objects (jewelry, furs, porcelain, etc.) donated by members of the public in memory of soldiers who had died. In 1918, the Diamond Syndicate — now the Diamond Trading Company (a.k.a. De Beers) — offered up this diamond for the sale. It was a match made in heaven, as the British Red Cross and the Order of St John uses the Maltese cross as its symbol.

The lot notes describe the sale of the diamond:

With its famous Maltese Cross through the table and with an unusual phosphorescence, it was presented to a packed saleroom on the 10th of April 1918 by the auctioneer, Mr. Anderson. Starting from £3,000, and after a fierce bidding war, the successful bid from the famous London firm S.J. Phillips made lot 377 achieve the staggering amount of £10,000.

£10,000 back then was the equivalent of about £600,000 ($701,000) today. It was the top lot of the sale, which ultimately raised a total of £50,000, or around £3 million/$3.5 million today.

The stone appeared at Christie’s again in 1973 — this time in Geneva — and sold for CHF 1.8 million, or about $4.3 million today. And now they’re offering it again, this time with a “significant” portion of the sale to be donated to the International Committee of the Red Cross.

The stone is listed as “estimate on request,” but Christie’s told National Jeweler they think it will go for “CHF 7 million to CHF 10 million, or about $7.5 million to $10.7 million.”

Holy cow. The Fine Jewelry Collections auction at Skinner ending on May 18 has a bunch of lovely antique items in it, but all thoughts of antiquity flew from my mind the second I saw this piece. This 14kt gold necklace features a GIGANTIC ARTICULATED PRAYING MANTIS with hinged legs that can be adjusted along the base wire of the piece. It’s got two cultured pearl accents and has an approximate interior circumference of 20.5 in. It would probably get caught on everything and be a huge pain in the ass. Still worth it. (Estimate $800-1,200.)

This 1956 Porsche 356 A 1600 Cabriolet has clearly seen better days, but that just makes it all the more desirable. (At least to me?) It’s included in the May 14th RM Sotheby’s sale in Monaco.

The car has been in the same hands since 1956, although it spent around five decades of that time parked in a barn in Denmark. The longtime owner, Esben A. Ubbesen, bought the car as a gift for his wife, and at some point before putting the car in storage, he replaced the 1.6-litre Porsche motor with a Volkswagen engine because of a leaking oil pan — but he kept the original Porsche motor, and it remains with the car today.

The lot notes claim the 356 Cabriolet was the “more aristocratic sibling of the legendary Porsche 356 Speedster…a true luxury sports car in its day,” and only 429 of them were produced in 1956. This 356 A model was upgraded with a new curved, panoramic windscreen that was introduced at the 1955 Frankfurt Motor Show.

Although RM Sotheby’s notes that Ubbesen regularly sprayed the car with oil “as a means of preserving body panels and mechanical components,” it’s still a mess — but scrolling through the photos makes my hands positively itch to fix it. Unfortunately it’s estimated at €150,000 – €180,000 ($159,000 – $190,000), so I won’t ever be doing that.

I know I already said “holy cow” earlier, but holy COW.

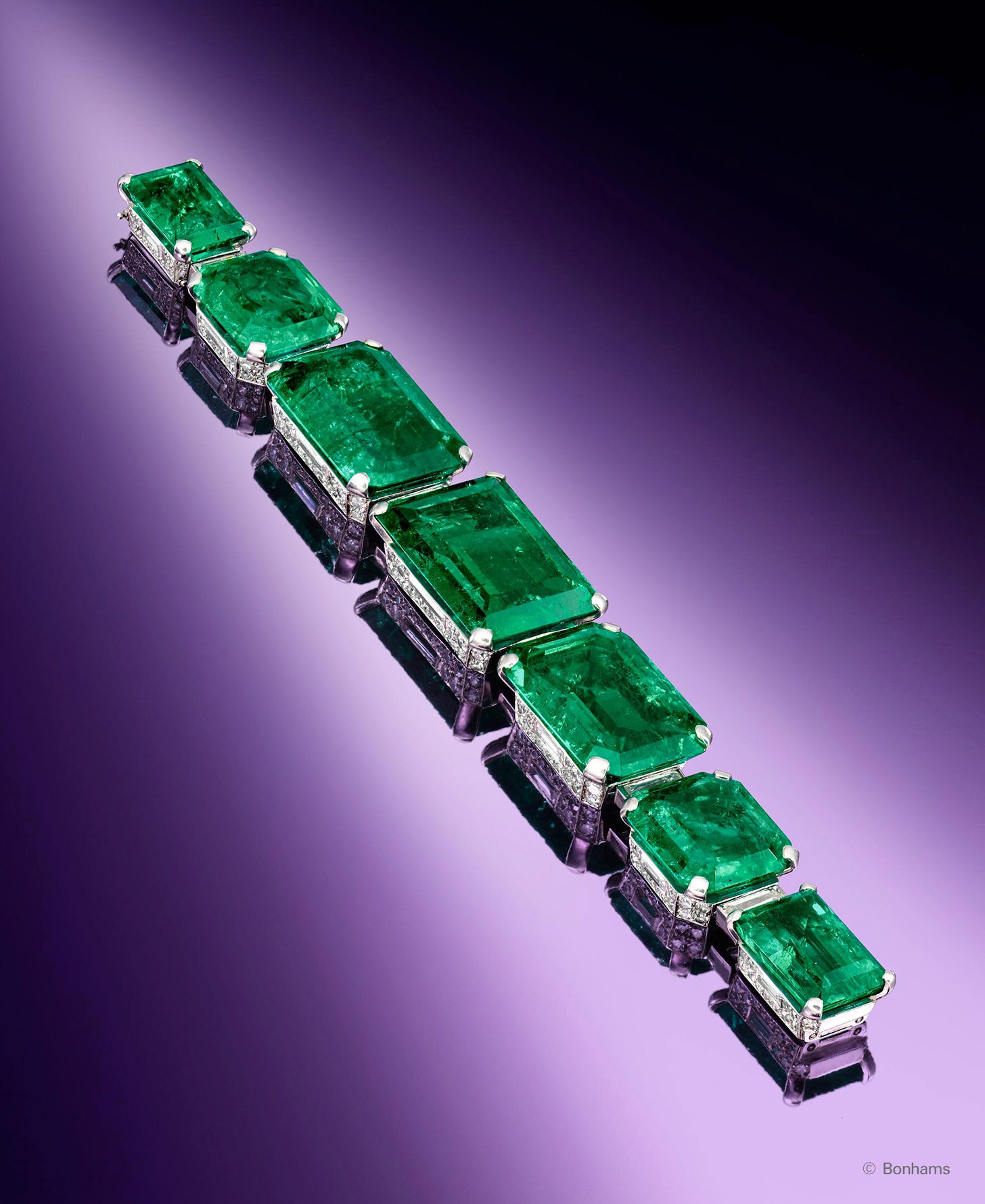

This circa 1926 Art Deco bracelet is by Cartier, and features a graduated row of seven rectangular and octagonal step-cut Colombian emeralds totaling approximately 101 cts. Set in platinum, the GIANT SLABS OF EMERALD are separated out by baguette-cut diamonds, with more baguette- and old European-cut diamonds nestled beneath.

The bracelet originally belonged to the fabulously wealthy American heiress Hélène Irwin Crocker Fagan (1887–1966). The daughter of a sugar baron, she later married Templeton Crocker (1884–1948), who was a millionaire librettist, yachtsman and grandson of the founder of the Union Pacific Railroad Company. According to Barron’s, Crocker basically introduced Art Deco to America by hiring Parisian designers like Jean Dunand to kit out his San Francisco apartment to great acclaim. (Some of his pieces now reside in the Met, but you can see a few photos of the apartment itself here in this Aestheticus Rex blog from 2011.)

Hélène divorced Crocker in 1928, stating that “his interest in his operas was greater than his interest in his wife.” WELP. Her bracelet, which is being offered in the May 24 New York Jewels sale at Bonhams, is estimated at $750,000 – $1,250,000.

Some happy news: The Friends of the National Libraries managed to drum up $1.25 million in two weeks in order to purchase a tiny book hand-made by Charlotte Brontë that surfaced at the New York International Antiquarian Book Fair late last month. They will donate it to the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth, Yorkshire.

Charlotte and her sisters Anne and Emily made these tiny hand-written and bound books when they were young, and Charlotte herself made more than two dozen of them. This one, “A Book of Ryhmes by Charlotte Bronte, Sold by Nobody, and Printed by Herself” was the last one known to be in private hands, and features 10 poems she wrote when she was 13 years old. The book had not been seen since 1916, when it was sold for $520 at an auction in New York, and its whereabouts were unknown until it was recently discovered “tucked in a letter size envelope stashed inside a 19th-century schoolbook” in an American private collection.

The anonymous seller — “a private individual who wishes to make certain of the work's future preservation” — offered the book through James Cummins Bookseller of New York City and Maggs Bros. of London, and the Brontë Parsonage Museum states that the manuscript will be “exhibited, available for study and digitized so that it can be made accessible to a worldwide audience.”

That’s all for now, pals. There’s definitely a lot of big, ostentatious stuff in this month’s missive, I realize! Sorry. There were a few other things I didn’t have space for, so I will have to figure out if they’re worthy of a follow-up free and/or paid email, or — who knows — maybe they just won’t seem as cool when I look at them in, you know, actual daylight. (I do wonder sometimes what these newsletters would look like if I wrote them at an hour that was not 3am. BUT I GUESS WE’LL NEVER KNOW HAHAHAHAHA)

Ok I’m out. Have a good week if that’s remotely possible.

Love you, M xx

Dearest is a monthly newsletter dedicated to the history of antique jewelry. Or, more accurately, dedicated to enthusiastically yelling about the history of antique jewelry. If you would like to offer your financial support for my nonsense, you are welcome to sign up for a subscription at $5 a month or $50 a year. The monthly email will always remain free for everyone, but as a paying subscriber you will also receive occasional single-theme emails highlighting interesting pieces that didn’t make it into the main newsletter due to issues of space or timing.

Hit the button below to sign up for a free or paid subscription, and thank you for being here!

Dearest is one of my favorite newsletters. Thank you for creating it, it's fabulous!

Delightful stuff—those emerald slabs! Your descriptions are phenomenal. Your eye is unerring. Thank you.