Hi guys. Hey look, a logo! It’s only taken me two years! To be honest, I’m amazed I was able to muster up even that small effort amid the crushing despair of seeing everything we’ve worked so hard for fade away. So much for all those big fall plans! Plus we’re kind of in the summer doldrums right now, auction-wise, so there’s not a lot of stuff that’s striking my fancy. Sotheby’s has an interesting selling exhibition of artist jewelry going on until August 28th, but they’ve only posted a pdf, which is annoying. (It’s worth clicking through to see some fun pieces by Alexander Calder,1 Max Ernst, Niki de Saint Phalle, Jeff Koons and others.) Since the auction pickings are slim, I’ve had a root through various dealer sites and museums for pieces that caught my eye. Read on to contemplate your mortality (more than you already are).

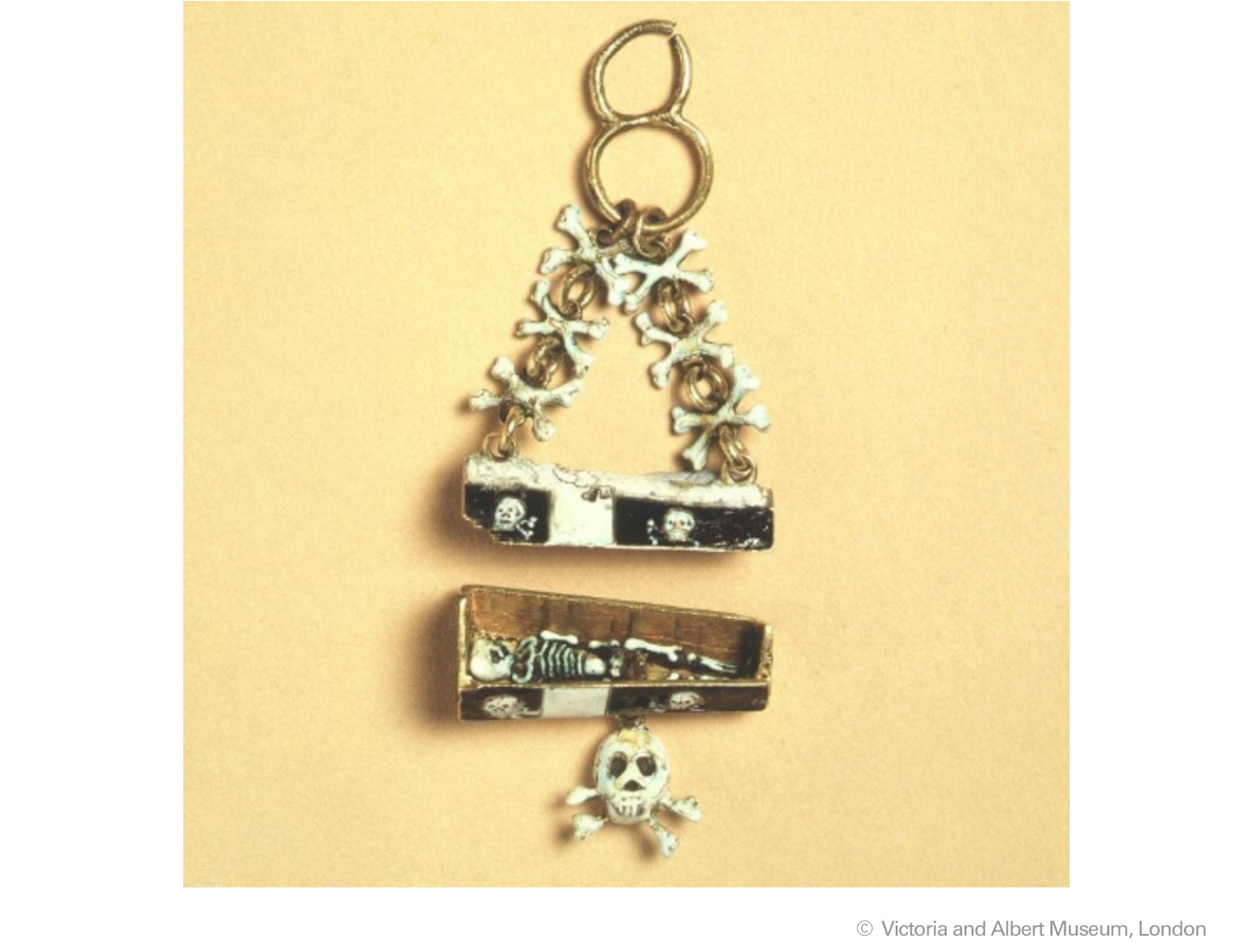

It’s been a while since I featured a memento mori (“remember you must die”) piece, and I particularly love this gold pendant in the collection of London’s Victoria & Albert Museum. Circa 1660, it’s German, and it takes the form of a black and white enameled coffin suspended by two chains. A skull-and-crossbones motif figures throughout — both on the coffin itself and hanging beneath — and a series of crossbones adorn the chains.

The coffin opens to reveal a tiny, enameled skeleton with the initials “I.C.S.” inscribed above its head, and there’s an additional German inscription that says: “HIE. LIEG. ICH. VND. WARTH. AVF. DIH.,” which the museum translates as “Here I lie and wait for you.” Yikes, ok.

The piece is part of a collection gifted to the V&A by Dame Joan Evans (1893-1977), the historian and former first woman president of the Society of Antiquarians. In her autobiography, Evans says, “I know, from my own work, how much the civilization of an age may be recorded in the history of trivial things,” and that PERFECTLY sums up why I love antique jewelry.

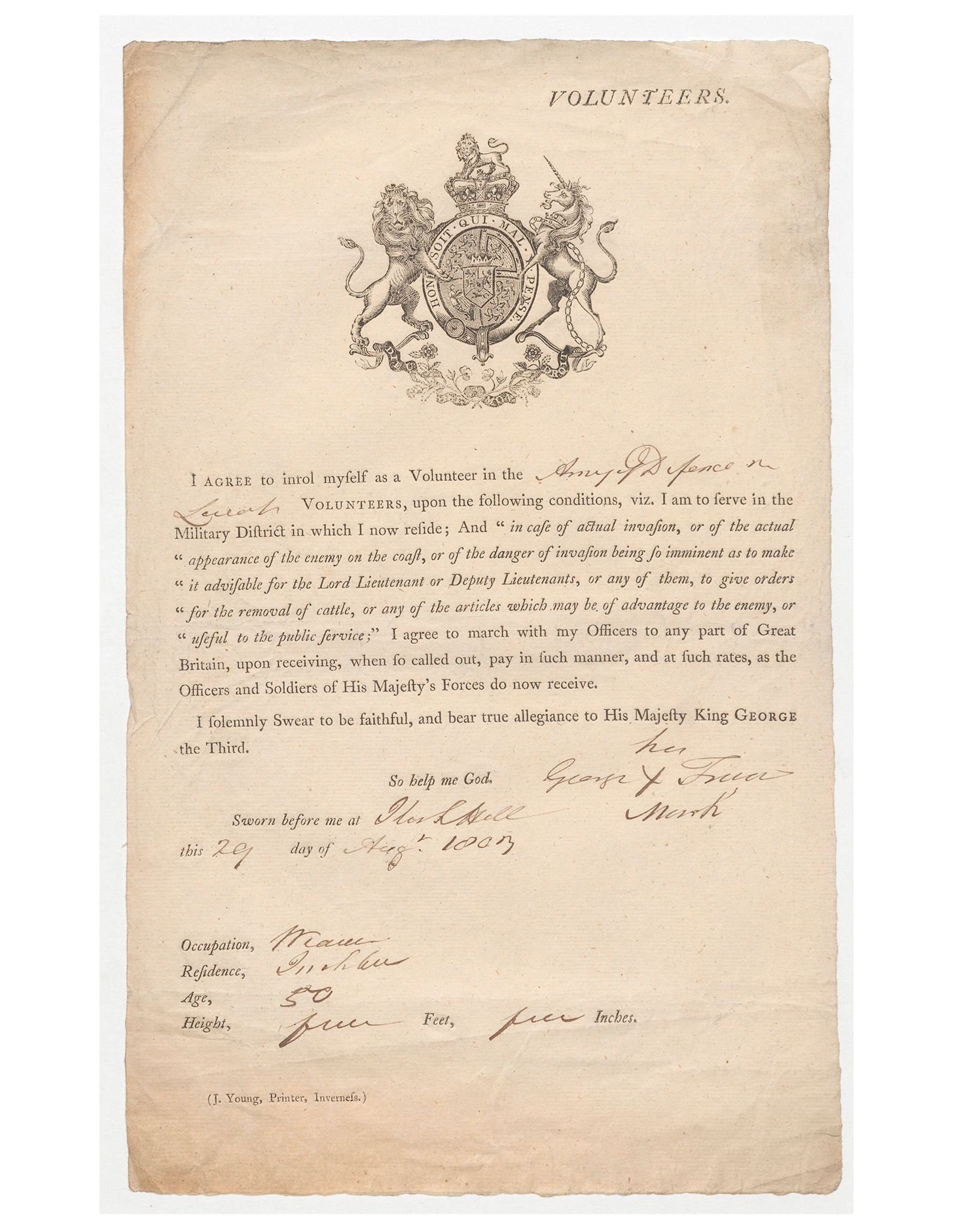

Following the French Revolution, Britain and France were almost constantly at war. They enjoyed a very brief period of peace in 1802, but the next year they were at it again, with Napoleon chomping at the bit to conquer Britain and the English building fortifications at the port of Dover and along the coastlines of Sussex and Kent.

Fear of an invasion led the English government to put out an official call for volunteers to bolster the existing army and militia, and the result soared beyond all expectations with nearly half a million men joining at its peak. Volunteers swore their allegiance to the King (see above) and planned to use their local knowledge to conduct small-scale guerilla warfare against invading troops.

The public sentiment is clear in this gilt metal pendant from 1803, which depicts a farm laborer brandishing a pitchfork at French warships in the distance, with the words “We are ready, Boney” painted above. The piece is being sold by London dealer Rowan & Rowan, who note that this is only the second such pendant they’ve seen since they’ve been in business.

“Boney” pendants weren’t the only type of jewelry to appear as a reaction to Napoleon. In 1804, the Royal Berlin Foundry began to manufacture household decorative items and furniture from iron, and eventually they also started producing jewelry — which came in handy in 1813–1815, when the Prussian royal family urged citizens to donate their gold and silver jewelry to help fund the war effort against Napoleon. In return, the citizens were given this new, intricate form of base metal jewelry, and many of the pieces were marked with the inscription Gold gab ich für Eisen (I gave gold for iron), or Für das Wohl des Vaterlands (For the welfare of our country/fatherland).

This jewelry — which was called “Berlin Iron” after its place of origin — continued to be worn and manufactured until the end of the century, and the styles progressed first from cameo-heavy neoclassical pieces to lacy, super intricate natural motifs, and finally to Gothic-inspired designs. The openwork patterns of the later styles meant the jewelry was surprisingly light, and because it was coated with black lacquer to prevent rust, it was also ideal for use as mourning jewelry.

The Georgian Berlin iron bracelets above — currently available at the Antique Jewellery Company in London — also feature what appear to be bands of Silesian wirework, a finely woven wirework mesh of iron that was produced in a foundry in Silesia (a region of Central Europe that incorporates parts of Poland, Germany and the Czech Republic) and often included in Berlin iron designs. Large cameos of Nike, the goddess of Victory, form the clasps and further the patriotic cause.

Circa 1840, this 14k gold watch key is topped by a cheeky little goblin. Watch keys were used to wind pocket watches, and much like vesta cases, they came in a huge range of designs — from fancy and bejeweled to fun, novelty or advertising pieces. Nowadays they’re often repurposed as pendants, and you can see some examples here on Ruby Lane. The little goblin was available at the always-interesting Erie Basin when I started writing this, but he has since sold. (As did this adorable little ca. 1960 castle turret charm.) If you ever see something you want at Erie Basin, don’t wait.

This 16th century German pomander is made of silver and features an ornately engraved exterior that’s full of references to the goddess Venus: cherubs, forget-me-nots, roses and gillyflowers (which are carnations, apparently?) as well as three panels that depict Venus herself, Mars and his mother Juno.

Pomanders have been around for centuries, and according to the dealer, Wartski:

The term pomander arose during the Middle Ages from the French pomme d’ambre and referred to an aromatic ball made of ambergris, civet, musk, dried flowers, spices and scented oils. In time, the term became interchangeable with the containers into which these scented substances were kept.

This pomander opens like a super fancy Terry’s Chocolate Orange to reveal a gilded, engraved interior and six hollow segments hinged to a central stem. Each segment has a sliding lid labeled for a specific substance, and the labels read: Canel (cinnamon), Negelren (cloves), Muskat (nutmeg), Schlag (a composite of ambergris, musk and civet) Bernstein (amber), Rosamarin (rosemary).

Miasma, or bad air, was long believed to carry disease (*laughs ironically*), and aromatic herbs and spices were often used to try to purify the air and mask rank scents. Inhaling certain spices was thought to ward off or even cure illnesses, and the Royal College of Physicians notes that doctors would often carry canes with pomander handles to protect themselves from catching plague or other diseases from their patients. Over time, the belief evolved to pair specific herbs or spices with specific ailments, so it was important to keep the spices separate — hence this pomander’s individually labeled containers.

Enough war and disease; let’s switch over to some contemporary stuff that has recently delighted me.

British jeweler Theo Fennell (who I’ve featured in the past) is famous for creating delightfully whimsical pieces that feature exquisite workmanship and an attention to detail that carries all the way through to the box design.

Above is his diamond-edged 18k yellow and red gold “Empty Quarter” ring, which features salamanders creeping up the shoulders and a dome that opens to reveal a tiny scene of camels traversing the desert. The scene was created by the ridiculously talented micro-sculptor Willard Wigan MBE, and the ring comes with a matching tiny, salamander-adorned magnifying glass to allow for a closer look.

Fennell has been through the ringer in recent years, as his company went public, became too big too fast, went into administration (basically bankruptcy, but in the UK) and weathered investors that were all about BRANDING *jazz hands*. Happily, the company has now come back under the control of its founder and namesake, and my friend and former JCK colleague Rob Bates talked to Fennell last month about the ownership uproar, the battle between creativity and business and the company’s new (old) direction. The future looks promising, as they get back to creating more individual pieces like the one above and away from branded jewelry that’s “like a cow with a brand stamped on its [backside].”

Last month, the venerable French jewelry house Boucheron unveiled their newest collection, “Holographique.” Creative director Claire Choisne introduced the collection by saying she wanted to offer the world “something joyful and bright,” and she set about doing so by combining traditional jewelry forms and materials with literal space-age technology. She says:

For this collection we’re offering a new approach around the holographic effect, where light creates an infinite range of colors. … To convey this holographic effect, we used two different means: Opals, which naturally have a holographic aspect, but also a technology used in the aerospace industry — it’s the spraying of a holographic coating of molten titanium and silver on which the shades of colors vary endlessly. Every piece of this collection is a prism through which white light is diffracted. Depending on the light or on the angle through which we’ll look at a piece, it will always look different.

The full collection consists of multiple suites, each with a different look but all playing on that overall holographic theme. The bracelet above is part of the “Halo” collection, which places holographic coating on the surface of softly curved rock crystal to mimic the “soft, comforting vibrations of a weightless soap bubble.” The piece is set in white gold and finished with diamonds.

I recommend looking through the whole collection — there’s an amazing necklace that was assembled from thin slices of rock crystal that took something like 600 hours to make, and another suite, “Faisceaux,” that places diamonds UNDER the coated rock crystal, so they softly gleam through from below. Some of the suites I like less than others, but they do manage to convey a sense of light and color that really is uplifting, at least to me.

Ok, that’s it! I hope this helped brighten your day. If you would like to support my work on Dearest, you can now sign up for a paid subscription, and I would like to send out a HUGE thank you to my subscribers — your support means everything. And thanks to all of you for continuing to read and share! Enjoy your weekend - M xxx

Why did Peggy Guggenheim pick up the phone? Because Alexander Calder! lol

Diamond Emerald Amethyst Ruby Emerald Sapphire Topaz???? 😭

That is a delightful logo. :)

Also, that 1803 pendant, the chap with the pitchfork - that could be on a Pro-Brexit poster from 2016, blimey...

I've just written something re. Napoleon and in digging, I was looking at British anti-Napoleon propaganda at the time, which was frankly...appalling? I mean, the London newspapers were publishing the most outrageous lies about him - plus, they intercepted his love letters to his wife (who was as increasingly cool and aloof with him as he was passionate and insecure-sounding to her) and the papers just absolutely went to town with them, full-page spreads of mockery. I can understand a lot of that volunteer patriotism: it's because the government portrayed him as someone every Brit could ridicule and hate. Not that Napoloen was great or anything, but- yikes. So easy with the distance of history to forget the power of whipped-up public fervour...